[i]

A SAILOR’S LIFE

[ii]

[v]

BY

ADMIRAL OF THE FLEET

THE HON. SIR HENRY KEPPEL

G.C.B., D.C.L.

VOL. III.

London

MACMILLAN AND CO., Limited

NEW YORK: THE MACMILLAN COMPANY

1899

All rights reserved

| CHAPTER LXVI | |

| PAGE | |

| Fatshan Creek | 1 |

| CHAPTER LXVII | |

| Visit Sarawak | 8 |

| CHAPTER LXVIII | |

| Sarawak—India—England | 11 |

| CHAPTER LXIX | |

| England | 19 |

| CHAPTER LXX | |

| England—Groom-in-Waiting | 32 |

| CHAPTER LXXI | |

| In Waiting | 36 |

| CHAPTER LXXII[viii] | |

| The Cape Command | 39 |

| CHAPTER LXXIII | |

| The Cape Command—Flag in Brisk | 45 |

| CHAPTER LXXIV | |

| East Coast Sport | 50 |

| CHAPTER LXXV | |

| Zanzibar—Shooting Hippopotami | 57 |

| CHAPTER LXXVI | |

| Zanzibar | 62 |

| CHAPTER LXXVII | |

| Forte—Flag Re-hoisted | 65 |

| CHAPTER LXXVIII | |

| The Cape Command | 68 |

| CHAPTER LXXIX | |

| Return to England | 75 |

| CHAPTER LXXX | |

| Shore Time | 80 |

| CHAPTER LXXXI[ix] | |

| Country House Visits | 92 |

| CHAPTER LXXXII | |

| A Shore Journal | 104 |

| CHAPTER LXXXIII | |

| Home Life | 109 |

| CHAPTER LXXXIV | |

| The Command in China | 113 |

| CHAPTER LXXXV | |

| Bound for China | 117 |

| CHAPTER LXXXVI | |

| The China Command | 129 |

| CHAPTER LXXXVII | |

| North China Ports | 139 |

| CHAPTER LXXXVIII | |

| Daibootz | 153 |

| CHAPTER LXXXIX | |

| The China Command | 164 |

| CHAPTER XC[x] | |

| The Outlook for the New Year | 173 |

| CHAPTER XCI | |

| Hari-Kari | 183 |

| CHAPTER XCII | |

| The China Command | 190 |

| CHAPTER XCIII | |

| Flag in Salamis | 206 |

| CHAPTER XCIV | |

| The China Command | 218 |

| CHAPTER XCV | |

| The Command in China | 227 |

| CHAPTER XCVI | |

| The Northern Ports | 237 |

| CHAPTER XCVII | |

| Memories of Gordon | 245 |

| CHAPTER XCVIII | |

| Yang-tse-kiang Trip | 256 |

| CHAPTER XCIX[xi] | |

| Chefoo to Japan | 263 |

| CHAPTER C | |

| The China Command | 272 |

| CHAPTER CI | |

| The China Command | 278 |

| CHAPTER CII | |

| Close of China Command | 285 |

| CHAPTER CIII | |

| Peking | 298 |

| CHAPTER CIV | |

| Homeward Bound | 311 |

| CHAPTER CV | |

| Last Visit to the Straits | 316 |

| CHAPTER CVI | |

| Some Farewell Notes | 321 |

| INDEX | |

| SUBJECT | ARTIST | PAGE |

|---|---|---|

| “Sibuko had had his Quietus” | E. Caldwell | Frontispiece |

| Part of my Galley’s Crew | Nina Daly | 3 |

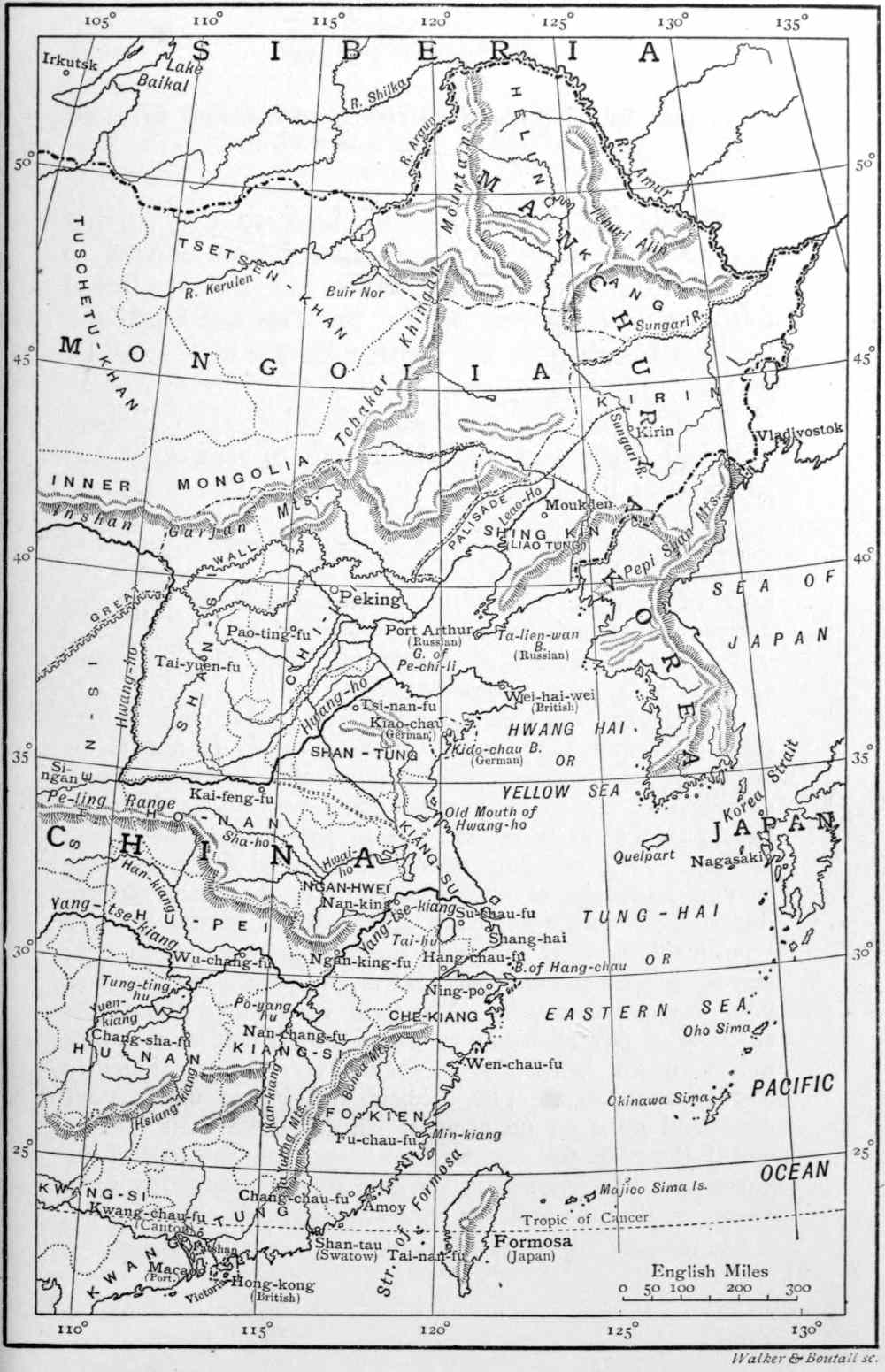

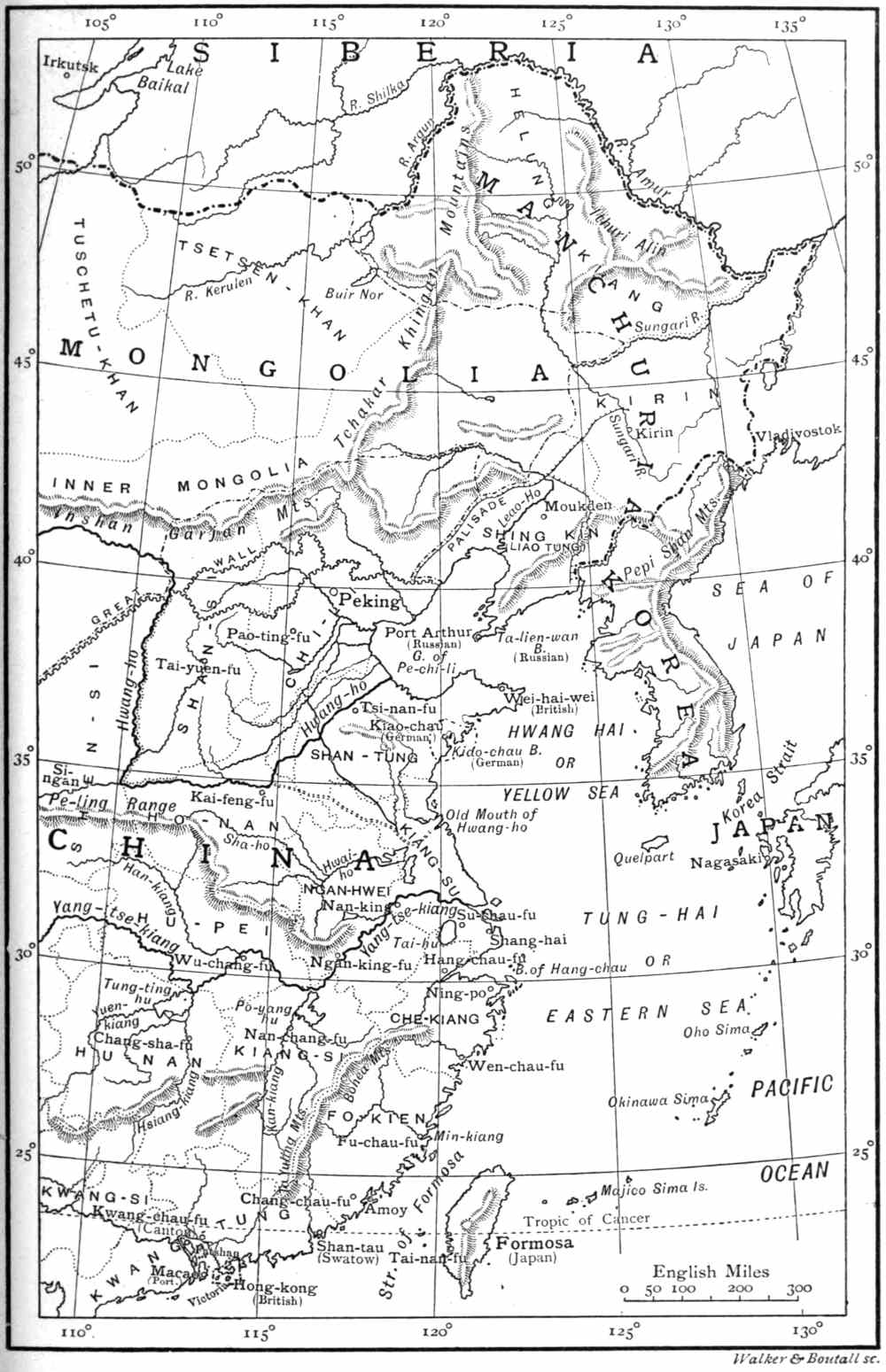

| Map—Northern China, with Coast of Siberia | 5 | |

| A Malay Kampong | Photo by Dr. Johnstone | 11 |

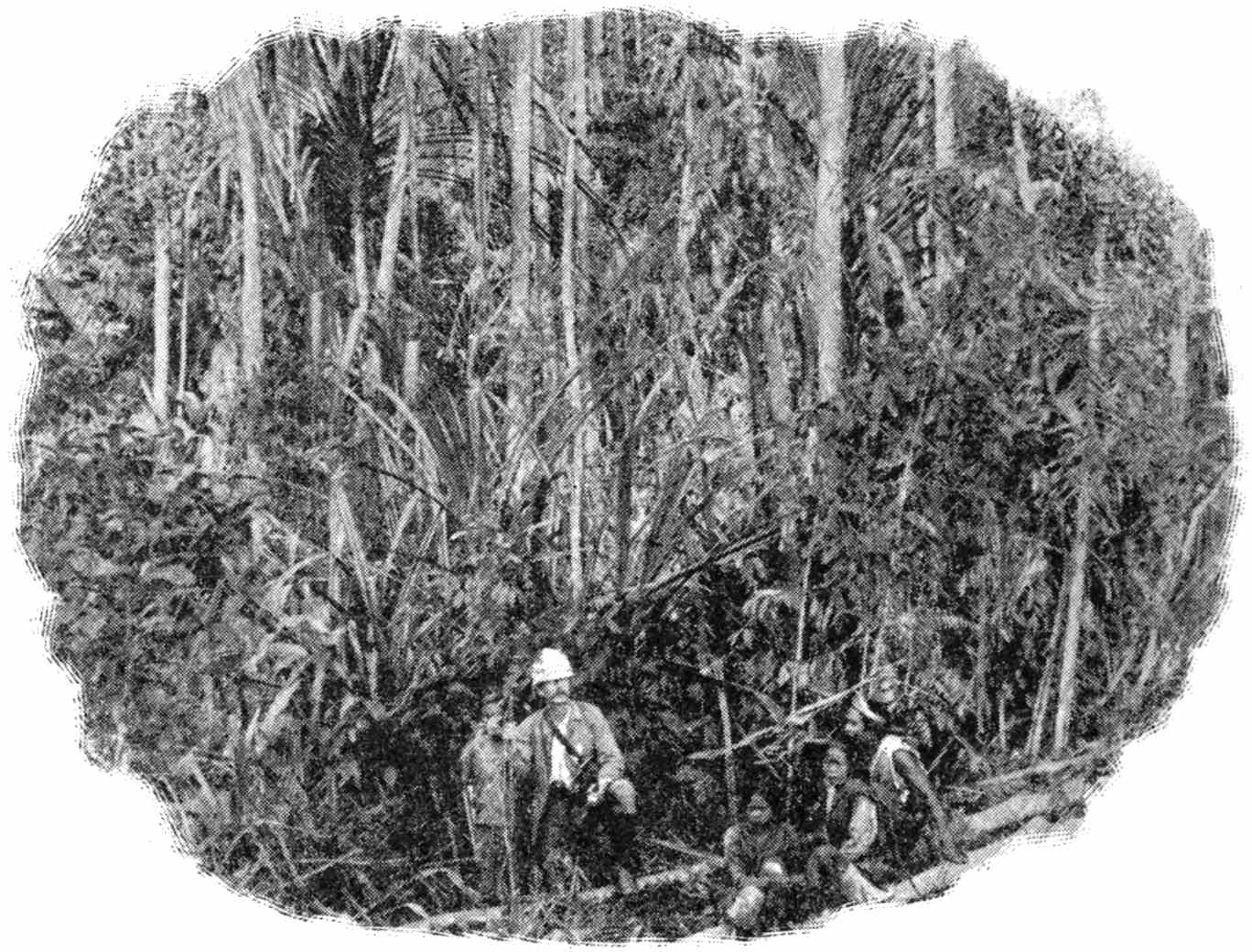

| In Bornean Jungle | ” ” | 12 |

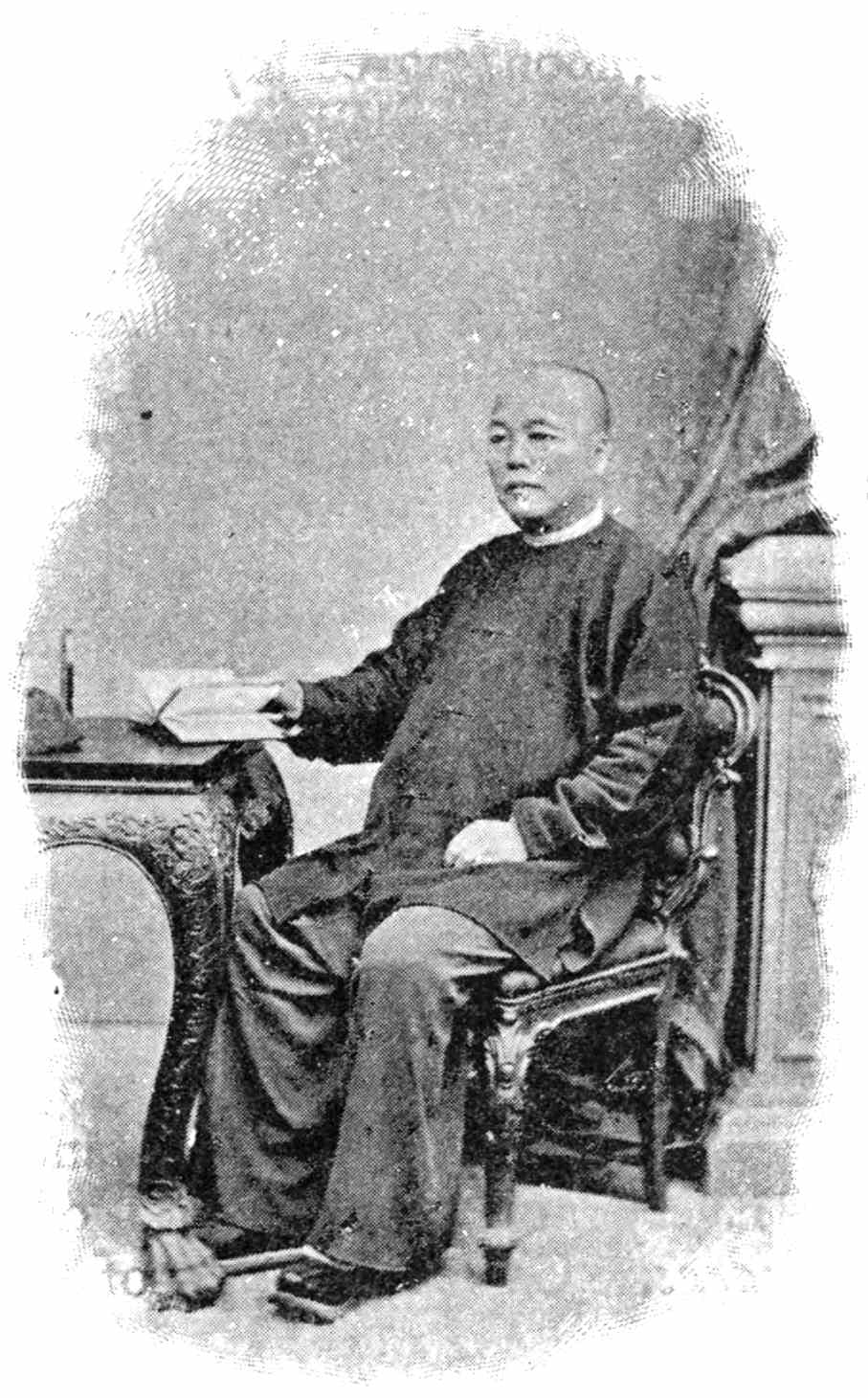

| Whampoa | Photograph | 13 |

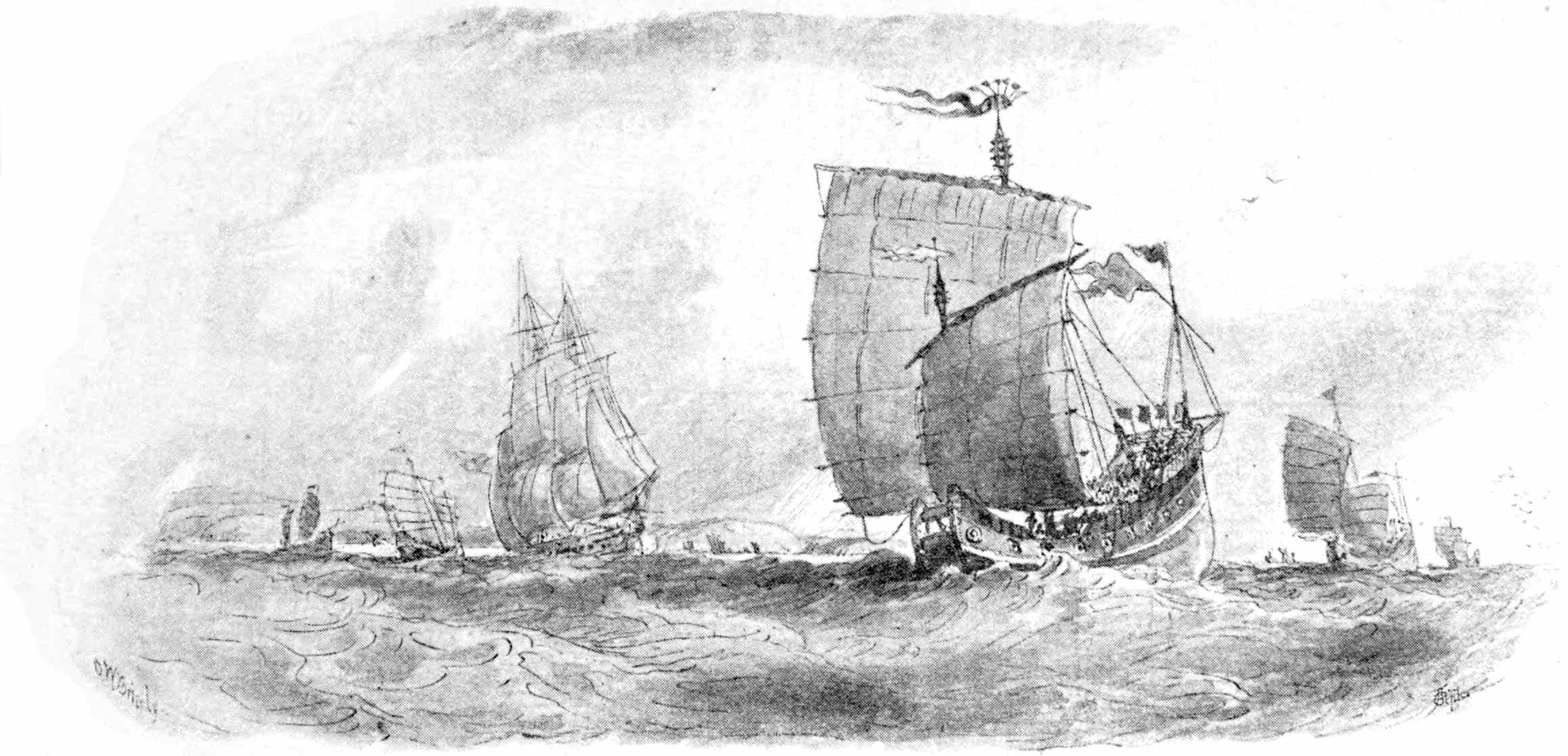

| Suspicious Junks | Sir Oswald Brierly | 21 |

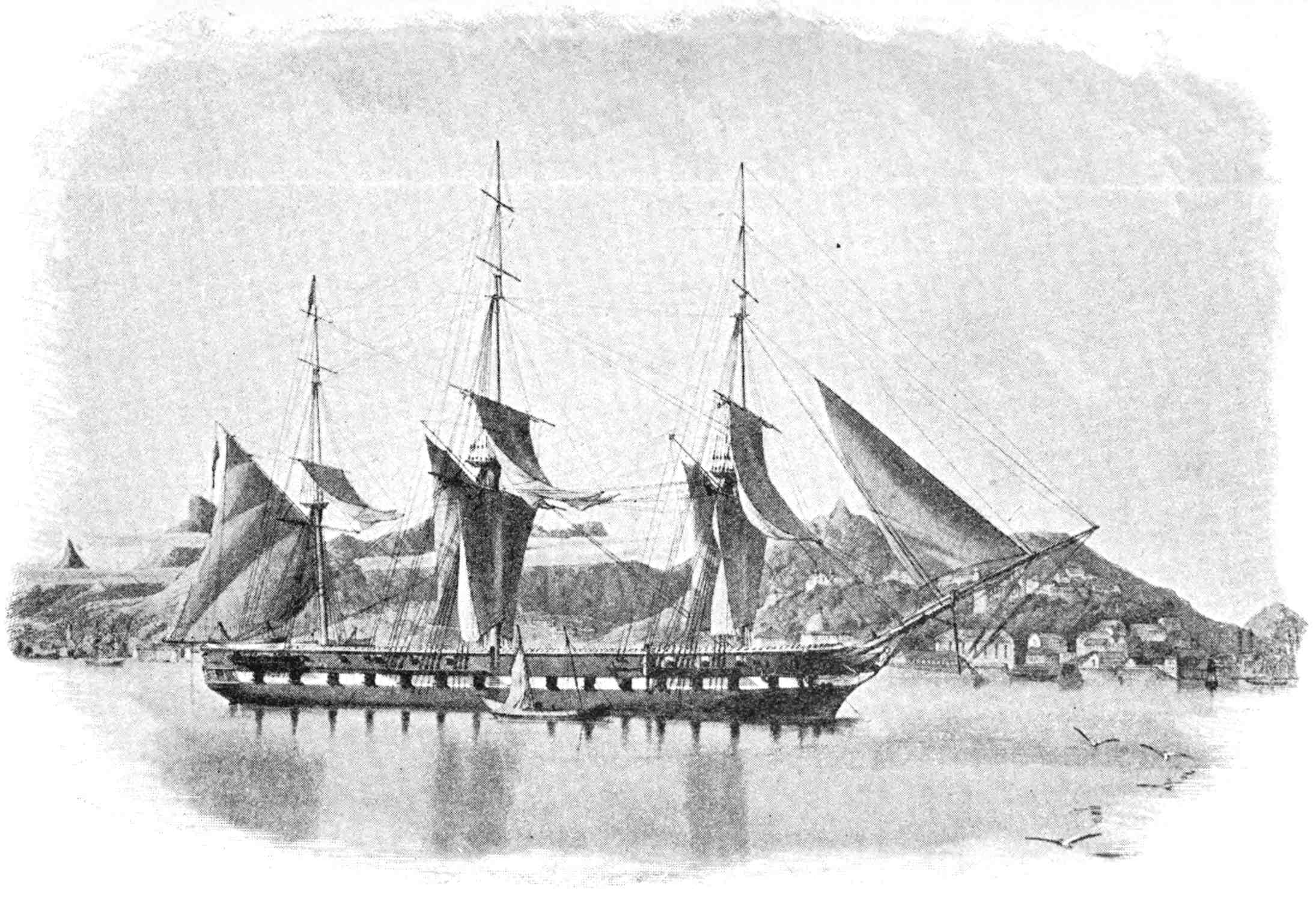

| Forte at Rio | ” ” | 43 |

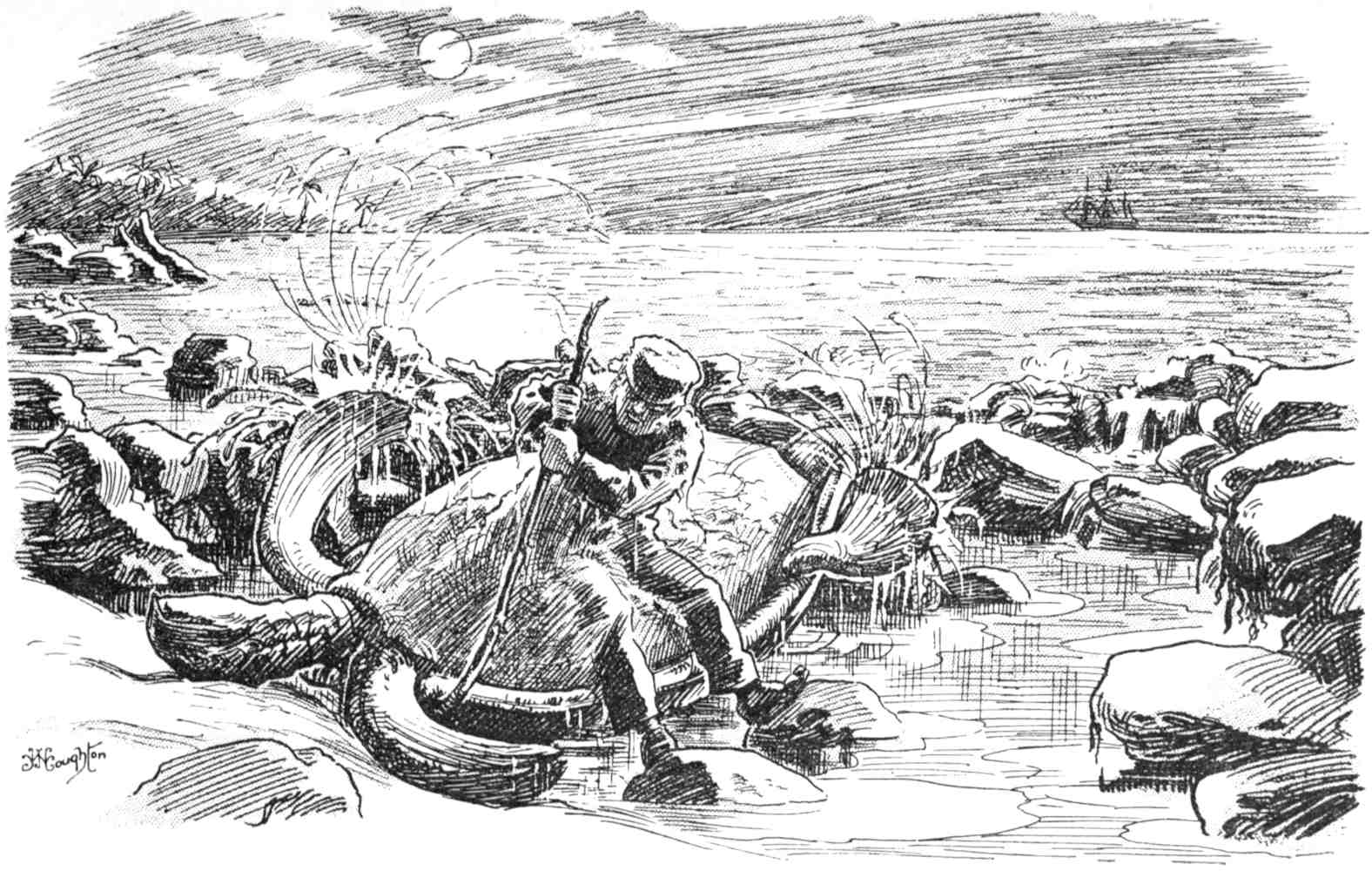

| My Middle Watch | J. W. Houghton | 53 |

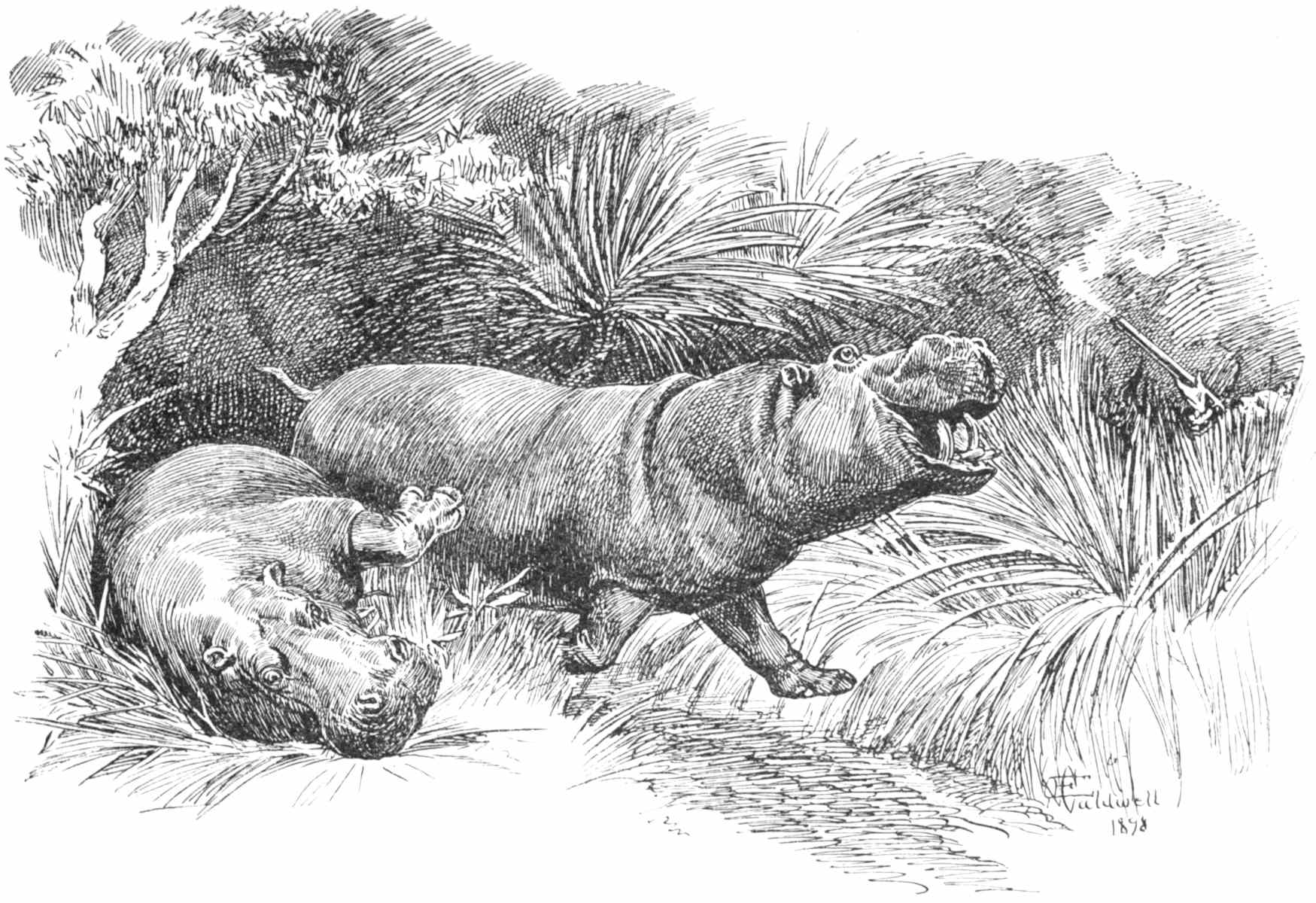

| A Right and Left Shot | E. Caldwell | 59 |

| Commodore Oliver Jones | Nina Daly | 129 |

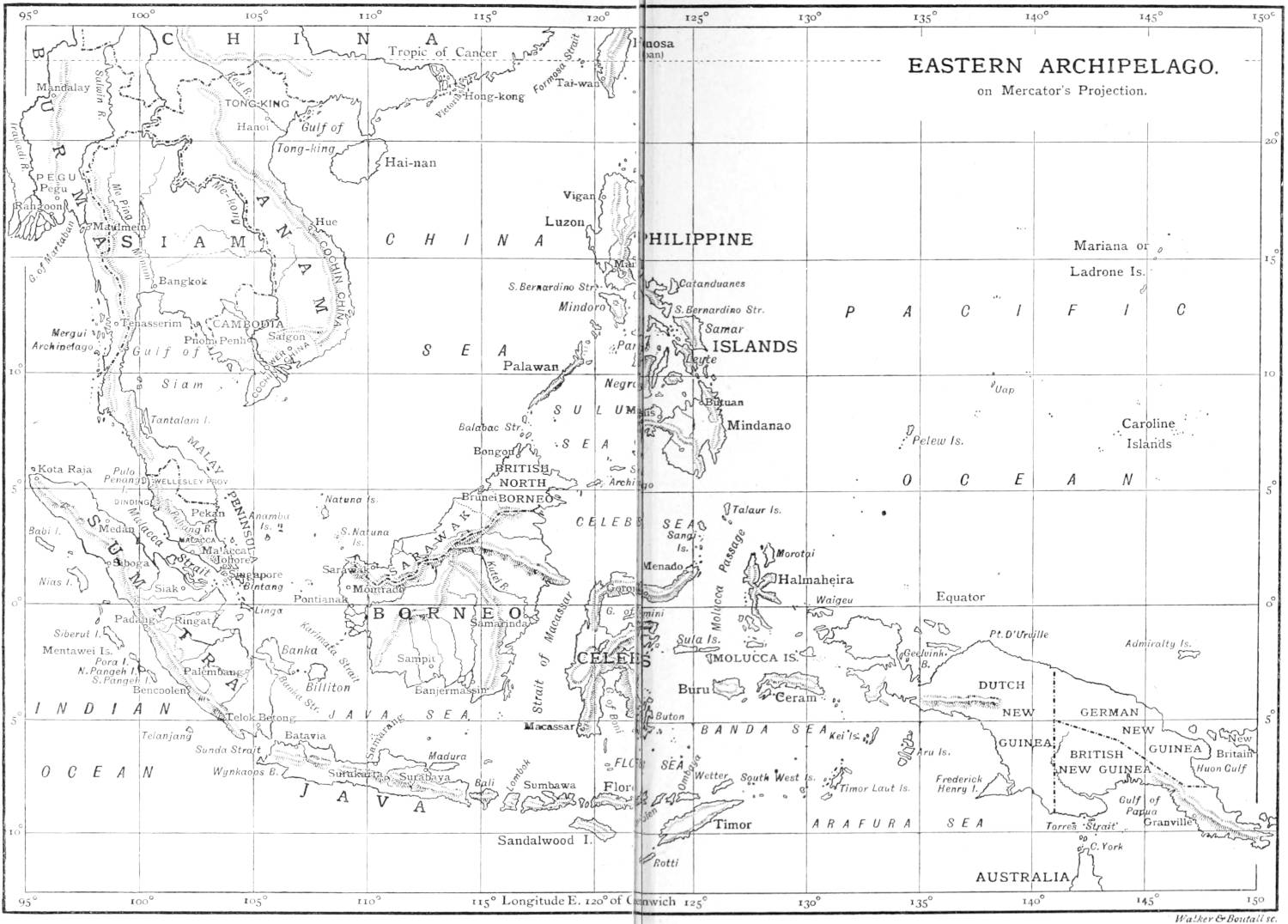

| Map—Eastern Archipelago | 142 | |

| Sir Rutherford Alcock | Photograph | 143 |

| Sir Harry Parkes | ” | 148 |

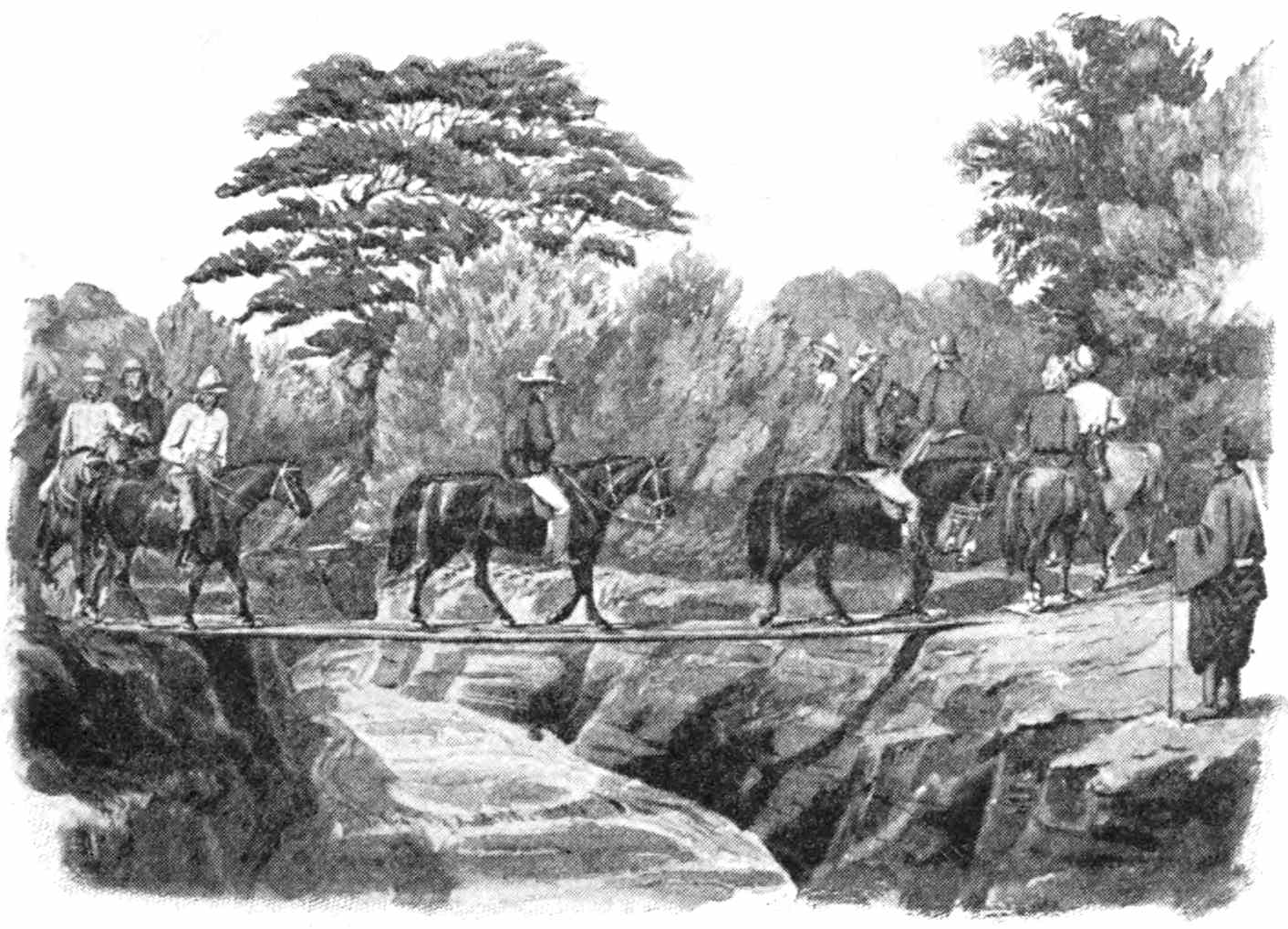

| Crossing a River in Japan | Commodore Oliver Jones | 161 |

| Lord Charles Scott | Nina Daly | 170 |

| Map—Northern China, with Coast of Siberia | 193 | |

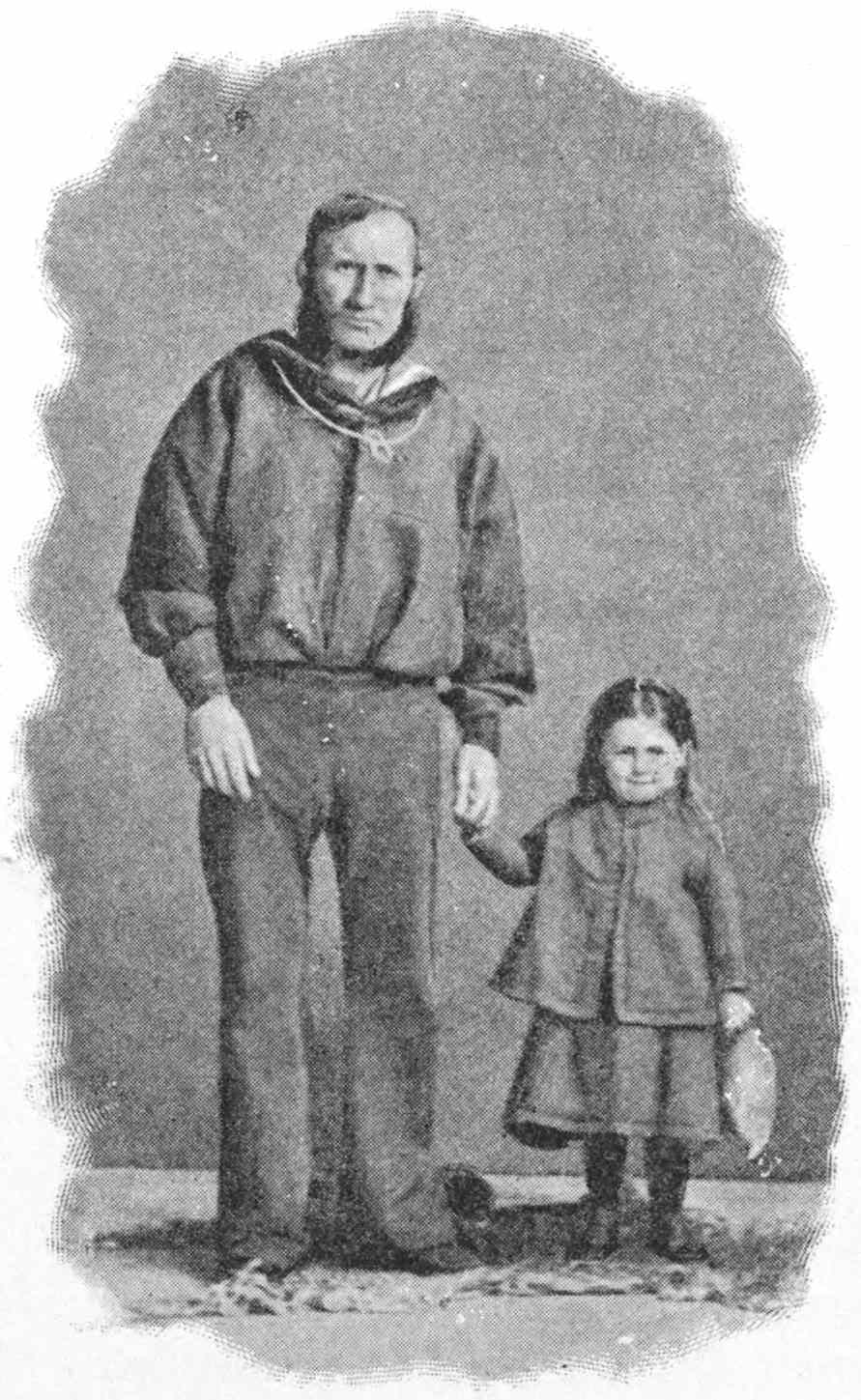

| May and Webb | Photograph | 248 |

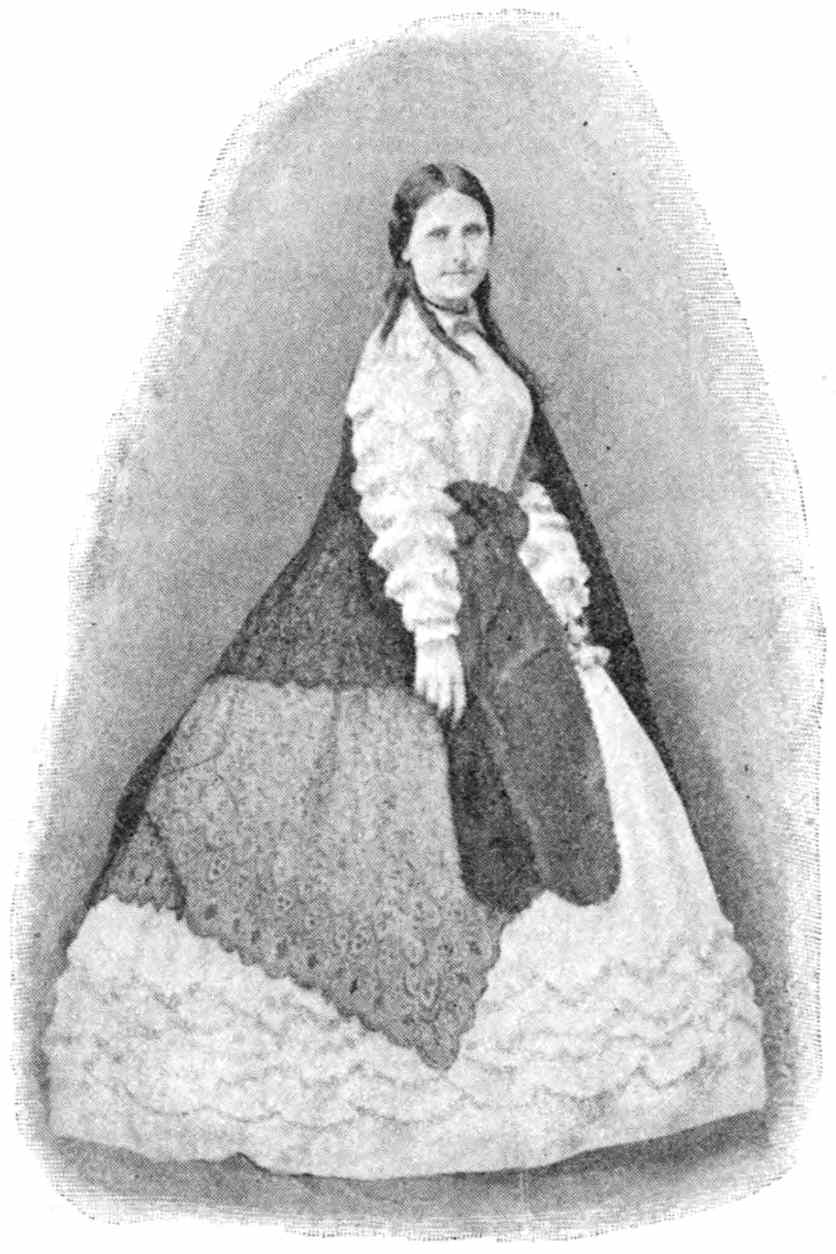

| Mrs. Alt | ” | 274 |

| The Prince who made the Omelette | ” | 305 |

| “The Little Admiral” | Hong Kong “Punch” | 314 |

| Jack Rodyk | Photograph | 319 |

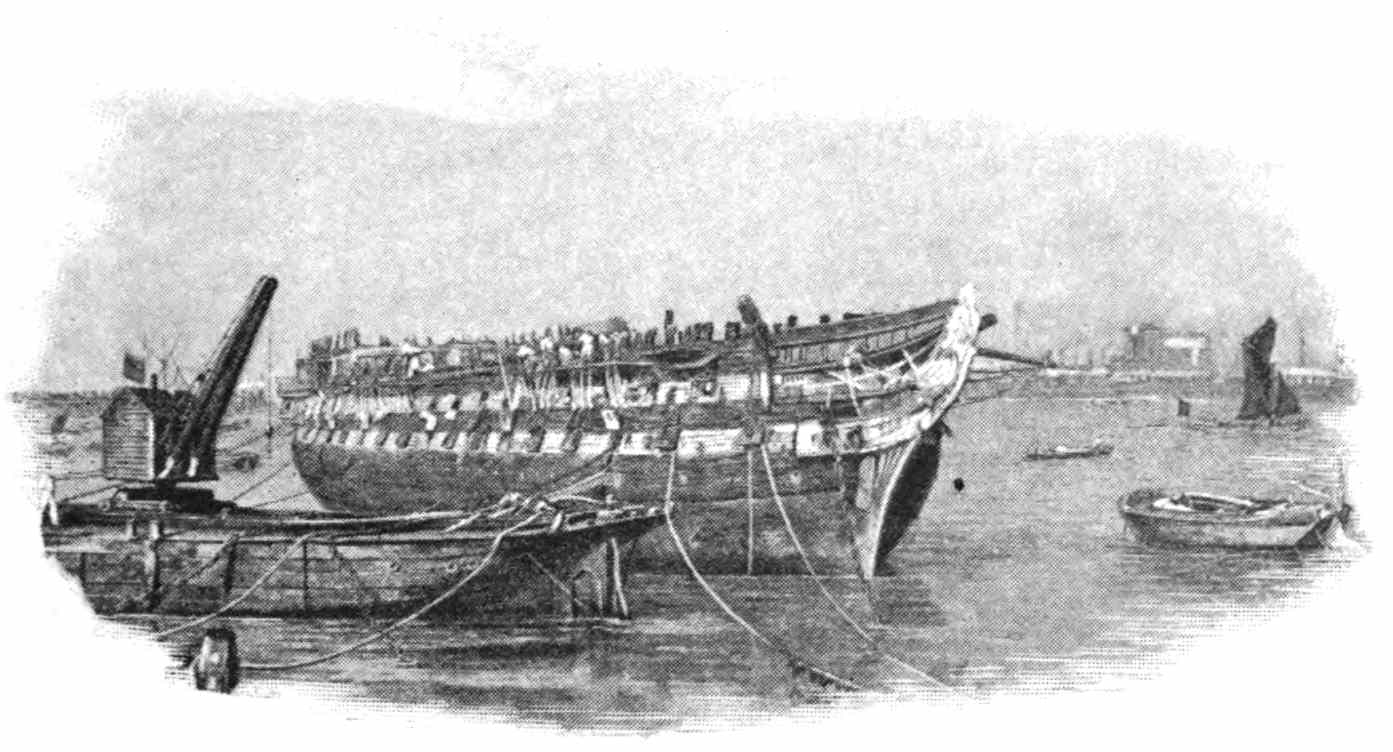

| Last of the Rodney, 1884 | ” | 323 |

| Duke of Buccleuch | ” | 327 |

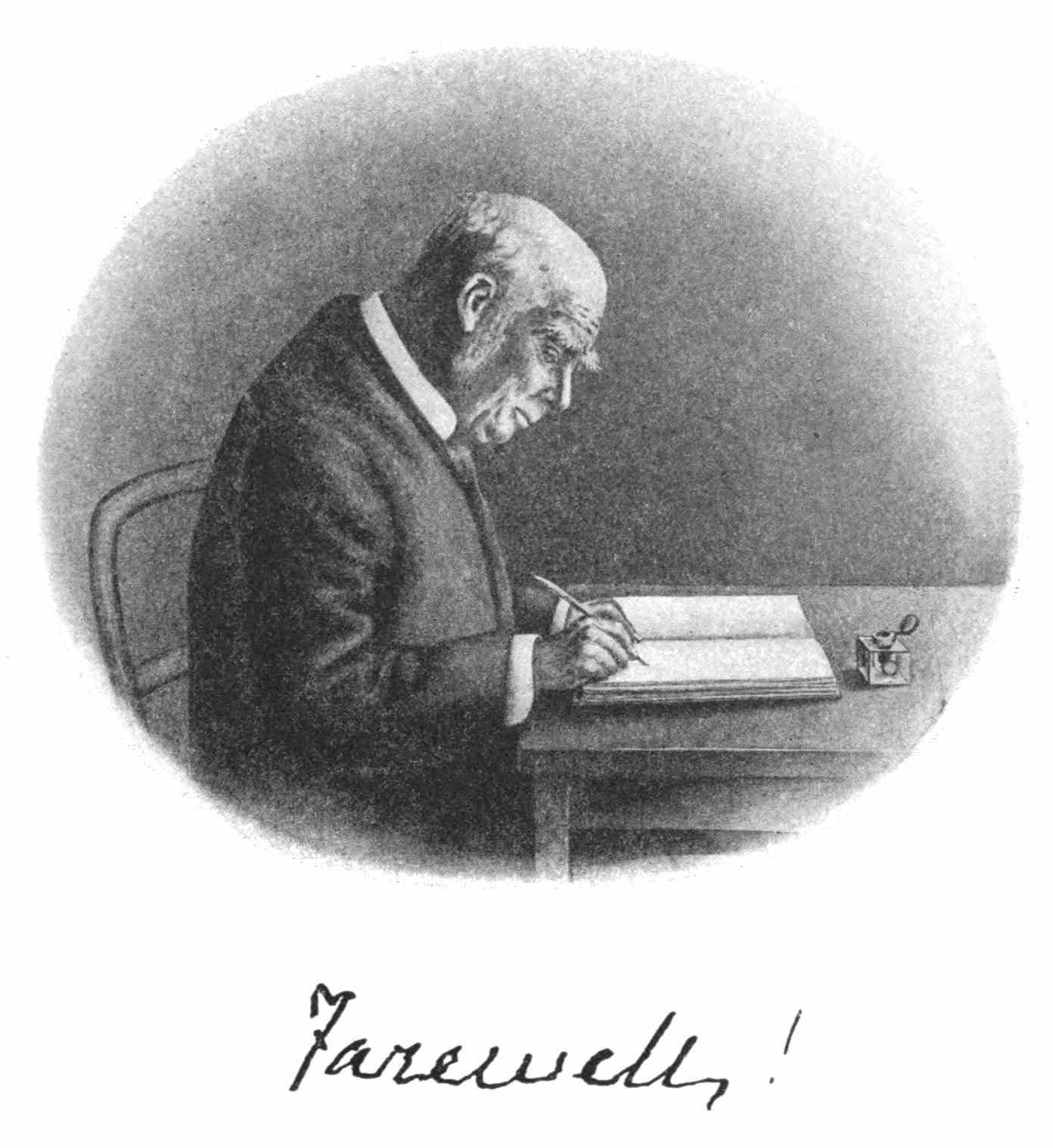

| Admiral of the Fleet, The Hon. Sir Henry Keppel, G.C.B., D.C.L. | Sketched at The Albany by Nina Daly | 335 |

Fatshan Creek

The time had arrived that the Admiral had arranged for the destruction of the Chinese Fleet. Prince Victor of Hohenlohe, my late aide-de-camp when I had the Naval Brigade in Crimea, was now with me as Commodore’s Flag Lieutenant. My gig only held one sitter besides self. Among my other boys I had on board the Hong-Kong with Goodenough were Lord Charles Scott, Victor Montagu, and Harry Stephenson. I left Commander Turnour in the Bittern to arrange my other boys. He had with him Lieutenant Stanley Graham, Dupuis, Foster, Pilkington, and A. V. Paget. In the Sir Charles Forbes were Lieutenant Lord Gilford and Hardy M‘Hardy. In the Macao Fort were Lieutenant W. F. Johnson and Captain Magin, Lieutenant Owen, Royal Marines, Hon. F. G. Crofton, and H. B. Russell, Master’s Assistant. My late youngster, “Jacko Hall,” in Childers brig was now Flag Captain: a strictly religious man.

Though everything was ready he had sufficient influence with our good chief not to desecrate the Sabbath, and so deferred the attack until Monday, the 1st of June, on which day I had the honour of [2] leading the boats of the Fleet in an attack on a strong force of the Imperialist junks posted in two divisions in well-selected positions in the Fatshan Creek. The following account is taken from a letter to my sister Mary:—

Alligator, Canton River,

June 20, 1857.

The three weeks of this month have been full of excitement. We commenced on the first with as pretty a boat action as can be imagined, though it may not be appreciated because it occurred in distant China. From the heights the Fatshan Creek affair must have been a beautiful sight. My broad pennant was hoisted on board the Hong-Kong. The shallow water caused her to ground; she would otherwise have been in front. Took with me Prince Victor of Hohenlohe, having previously been commanded by Her Majesty, through Sir Charles Phipps, to take every care of him, and left Victor Montagu, my proper gig’s mid, on board; but the lifting tide soon put him in the midst. We took the lead. The first division of the Chinese were attacked simultaneously by about 1900 men. I had not more than a quarter of that number to attack the second division, which was three miles higher up the river in a well-selected place, evidently the élite of their Fleet. The junks numbered twenty in one compact row, mounting about fourteen guns each, removed to the side next us, those in the stern and bow being heavy 32-pounders. Boarding nets were dropped on our boats, but not until our men were alongside, as it enabled them all the quicker to sever the cables connecting the junks. Raleigh’s boats well up, and did not require cheering on. The Chinese fired occasional shots to ascertain exact distance, but did not open their heaviest fire till we were within 600 yards. Nearly the first poor fellow cut in two by a round shot was an amateur, Major Kearney, whom I had known many years. We cheered, and were trying to get to the front when a shot struck our boat, killing the bowman. Another was cut in two. A third shot took another’s arm off. Prince Victor [3] leaned forward to bind up the man’s arm with his neck-cloth. While he was so doing, a shot passed through both sides of the boat, wounding two more of the crew; in short, the boat was sunk under us.

Our man-of-war boats do not carry iron ballast, but are steadied by “breakers” made to fit neatly under each thwart and filled with fresh water. The tide rising, boats disabled, oars shot away, it was necessary to re-form. I was collared and drawn from the water by young Michael Seymour, a mate of his uncle’s flagship, the Calcutta. We were all picked up except the dead bowman, whom the faithful dog “Mike” would not leave. As we retired I shook my fist at the junks, promising I would pay them off. We went to the Hong-Kong and re-formed. I hailed Lieutenant Graham [4] to get his boat ready, as I would hoist the broad pennant for next attack in his boat. I had no sooner spoken when he was down, the same shot killing and wounding four others. Graham was one mass of blood, but it was from a marine who stood next to him, part of whose skull was forced three inches into another man’s shoulder. When we reached the Hong-Kong the whole of the Chinese fire appeared to be centred on her. She was hulled twelve times in a few minutes. Her deck was covered with the wounded, who had been brought on board from different boats. From the paddle-box we saw that the noise of guns was bringing up strong reinforcements. The account of our having been obliged to retire had reached them. They were pulling up like mad. The Hong-Kong had floated, but grounded again. A bit of blue bunting was prepared to represent a broad pennant, and I called out, “Let’s try the row boats once more, boys,” and went over the side into our cutter (Raleigh’s), in which was Turnour and the faithful coxswain, Spurrier. At this moment there arose from the boats, as if every man took it up at the same instant, one of those British cheers, so full of meaning, that I knew at once it was all up with John Chinaman. They might sink twenty boats, but there were thirty others who would go ahead all the faster. It was indeed an exciting sight. A move among the junks! They were breaking ground and moving off, the outermost first! This the Chinese performed in good order, without slacking fire. Then commenced an exciting chase for seven miles. As our shot told they ran mostly on to the mud banks, and their crews forsook them. Young Cochrane in his light gig got the start of me, but, having boarded a war junk, John Chinaman did not wait to receive him properly, but preferred mud on the other side. Seventeen junks were overtaken and captured. Three only escaped. Before this last chase my poor Spurrier was shot down. I saw his bowels protruding, with my binoculars in the middle, as he lay in the bottom of the boat, holding my hand. He asked if there was any hope. I could only say, “Where there is life there is hope,” but I had none! He was removed into another boat, and sent to the hospital ship. Strange to say, the good Crawford served him up, and the Admiral’s last letter from Hong-Kong [6] states that Spurrier hoped to return to his duty in a few days.

Words fail me, on looking back to this stirring day, to express my gratitude that I was allowed to take part in this action. When my ship was lost, I felt as if my day was done. But fate was kind, and Fatshan Creek gave me another chance in the service I ardently loved.

The following proclamation, by the Chinese Admiral Yeh, was found in one of the captured junks after Fatshan:—

Liang, subaltern in charge of the Tan chau[1] Station of the Kwang Tung Province, whose name is noted for the rank of captain, with authority meanwhile to wear the button of that rank, makes a communication.

“I am in receipt of a despatch from the Governor General Yeh, to the following effect:—

“‘Whereas the barbarian outlaws[2] have not as yet submitted, and the nature of these rebels is not to be fathomed, the officers and men of the different vessels stationed at P’ing-chau[3] must stand well and strictly on their guard, so as to be ready at all points, and prevent any mishap. It is my duty, therefore, to send orders at once to you, on receipt of which you will, in obedience thereto, immediately confer with the other officers associated with you on this service, and with them set an example in concerting proper measures of control and precaution on board your respective vessels. You will continue without distinction of day or night to patrol constantly, as a shuttle moves in the loom, and to make observation assiduously and with secrecy. The soldiers and braves under your command must on no account land, or leave their vessels; and if there be the slightest movement on the part of the barbarians, you must make for Sam-shan and open fire upon them, cutting off and slaying ruthlessly. If any one ruin [7]the undertaking by venturing, be it ever so little, to be slack or indifferent, the officer commanding shall be held responsible; no mercy shall be shown him. Courage in the engagement shall be liberally rewarded. Haste in fear! Haste in earnest!’

“In obedience to the above I write to every other of the officers in charge of vessels. In addition to this it is my duty to write also to you; I accordingly write and request that you will in no particular depart from the instructions of His Excellency.

“A necessary communication addressed to the officer in charge of the Shun-on Li junk.

“Hien Fung, 7th year, 5th moon, 8th day (29th May, 1857).”

[1] In Hai-nan.

[2] Fi, vagabonds, rebels, or any lawless persons.

[3] Between Sam-shan and Fat-shan.

[8]

Visit Sarawak

Master and self tried by court-martial on board the Sybille for the loss of the Raleigh.

The hull of my poor Raleigh advertised for sale, to take place on Monday 29th. Who would have believed it! Commander-in-Chief appointing us by commission, dated yesterday, to the Alligator.

Sunday.—My birthday. Enter my forty-ninth year—a day on which one no longer cares to be congratulated. Went up in Hong-Kong as far as Second Bar, where Tribune and Highflyer are.

Proceeded to Macao Fort; found they had made a prize of a mandarin junk laden with tea.

Returned as far as Second Bar and met Sampson. No permission from Chief to ascend Anninghoy Creek.

Made preparations for capture of the Chucupee Fort. The Celestials, however, mizzled on our approach. Took possession and left Edgell with Tribune in charge.

Anniversary of Her Majesty’s Accession. Dressed ships. At noon fired Royal salutes the whole length of the Canton River.

Shifted berth to below Second Bar, taking old Alligator up. Dined with Sir Robert M‘Clure of North-West Passage celebrity in Esk.

[9]

Friend “Thomas,” Prince Victor, and self took departure for Dent’s comfortable quarters at Macao, on board the Firmee. Found poor Cleverly still confined to bed. Met a clerk of Dent’s House, who wears a moustache, and looks a muff.

Macao better climate than Hong-Kong. Thomas, Prince Victor, and I dined at Endicott’s.

Heard of the untimely death of poor young Foster, which took place on board the Fury off Macao Fort. By Firmee to Hong-Kong and Dent’s bungalow. Visit from St. George Foley.

Returned by Firmee to Macao, meeting Admiral there in Coromandel, who informed me of the little chance I had of becoming second in command, as far as Sir Charles Wood was concerned.

Mail in from England. Ascertained from Commander-in-Chief that Sir Charles Wood at Admiralty disapproved of my broad pennant being hoisted after loss of Raleigh. Decided on going home.

The worthy Judge Hulme gave me a farewell dinner. Parting dinner at Dent’s. William Dent over from Macao.

Took leave of my good friends the Dents. Also the kind Admiral. Embarked on board Formosa, P. and O. steamer, for passage to England, with option of landing and coming on when and how I like. Flagship manning rigging and cheering on passing. My Raleigh’s officers on board, with others, to wish me good-bye!!!

Once more on the wide and open sea, but in the novel position of passenger. Dr. and Mrs. Parker and my worthy friend and old shipmate Crawford of the party.

10 A.M.—Arrived in New Harbour, Singapore. [10]Kindly taken in by Blundell at Government House. Read Clarence Paget’s friendly explanation of my recall in the House of Commons.

Found Charlie Grant, wife and child, going to Sarawak.

Dined with the Blundells—their daughters, Jane and Anne, particularly nice girls.

Emperor steam yacht in the Roads requiring a foremast—time for her to take me to Sarawak and return while mast getting ready. Pleasant and convenient arrangement. News from India; slight improvement, but Delhi still untaken.

Captain Sidney Grenfell, senior officer in Malacca Straits, cancelled the orders already given. The Emperor of Japan’s yacht is not to go with me to Borneo! There is a difference between being in and out of office.

Dined with Colonel Liardet at the mess of 21st N.I.

Lord Elgin arrived from Calcutta in Ava, P. and O. Co’s steamer. Breakfasted with Harvey, meeting Greenshields and Paterson, with their wives.

Many good fellows in Lord Elgin’s staff, George Fitzroy one of them. Dined at home (Government House) to meet Lord Elgin.

Mail in from England. Turnour and Prince Victor promoted. I senior captain on the list. Many letters of congratulation on Fatshan Creek. Met Lord Elgin and party at dinner.

Embarked on board Emperor of Japan’s yacht.

Rounded Taujong Datu. In evening anchored off Taujong Poe.

[11]

Sarawak—India—England

Piloted the yacht as far as the Quop. Up in the gig to Sarawak. How altered! Extended but not improved in appearance. Miss the attap roofs; tiles look heavy. Miss the jungle, and, most of all, the Rajah, who is at Brunei.

Brooke Brooke and Charlie Grant are here with their wives, and each owns a child. How many happy associations of bygone days. Must wait Rajah’s return. Dine with the Bishop. Took a stroll in the jungle with Alderson’s rifle. Jungle too magnificent. Found the walking bad, and the gun heavy, to say nothing of the wood-leeches that adhered to and feasted off my legs, in spite of my trousers being tied like bloomers round the ankles.

Took an early walk over two miles of the road [12]cut through the jungle. Somewhat checked by Chinese outbreak. Plenty of wild pig about, but difficult to get at.

Went to church. Service performed by Bishop, with three assistants. Singing by native Christianized children wonderfully good. Young Brooke and I dining with the Bishop—a good fellow, without guile or humbug.

Crossed the river to see a man-eating alligator just caught, length 12 ft. 6 in. Astonishing the ease with which the Malay kris cuts through the thick skin between the joints along the neck and tail of the brute. Started with Charlie Grant, Alderson, and Watson in an excursion up the river by P.M. tide.

Grant having put us up in his bungalow, where he is about to build a fort and assume the command of [13]that district, we started in afternoon on our deer-shooting excursion, getting as far as the Singy Hill Dyaks, where we slept in their “scullery.” Unclean animals these Dyaks.

A forenoon walk took us some four or five miles to a hut near the deer ground. In afternoon, before sunset, we went out in two parties. Saw some large red deer; stalked near and shot a doe.

Long walk of ten miles in the hottest sun, and roughest ground. Back to boat. On arrival at bungalow, heard of Rajah’s return to his capital. Started alone after dinner for Sarawak to join him. Found Brooke in great force; nearly five years since we met; he altered, but not so much as I expected, considering smallpox and what else he has gone through.

Embarked on board the Sir James Brooke on return to Singapore. Farewell, Sarawak. May you prosper as you so well deserve!

Arrived in Singapore. Governor being absent at [14]Penang, put up at Whampoa’s, and how comfortable the good fellow made me!

Waited on by a deputation of the merchants to invite me to an entertainment. Grand dinner given by the residents at the London Hotel. Their kindness preventing my responding as I wished.

Afternoon agreeably passed at Angus’s small bungalow, where Whampoa, “Thomas,” Briggs, and Harrison dined.

Dined with Napier. Anniversary of his wedding, at which I was present thirteen years ago.

Mail steamer coming in, decided on going on. Find myself on flag list, also recommended for the K.C.B. 4 P.M., embarked on board Cadiz, mail steamer.

1.40 P.M., arrived at Penang. Dined with old friend Lewis, having called on Blundell and the recorder, Sir Benson Maxwell. On board at 6; Cadiz under weigh.

Arrived at Galle before 8 o’clock. Took rooms on shore, but as the P. and O. agent was not inclined to let us proceed by way of Bombay without extra payment, accepted an offer to go to Bombay in Madras hired transport. Packed up and off again by sunset.

Every attention paid to our comfort on board Madras. Captain Jenkins of the Indian Navy most kind.

10 P.M., came to in Bombay Harbour.

Landed after breakfast, having received an invitation to take up my abode with Captain and Mrs. George Wellesley, he in charge of the Bombay Marine. They had a sweet little girl I called the “Râni.” Sir Hugh Rose was here on his way to the Mutiny, having already been home since the Crimea. He was staying with the Governor, Lord [15]Elphinstone, on the hills at Matheran, where I joined them later. Came up, too, with our invalided Doctor Crawford, who found his brother here, a magistrate, with whom I had a good dinner. We went by train to see the wonderful elephant caves with fittings that date two thousand years before the birth of our Saviour.

Kindly welcomed by Lord Elphinstone. So glad to have a few days with Hugh Rose. Pleasant party, consisting of Captain Colborn and staff. Climate delightful. Blankets pleasant. No mosquitoes.

At breakfast appeared remainder of staff, Doctor Peel and Colonel Bate. Rode with Governor in cool of evening. Such varied and magnificent scenery! Rode some eight miles without a hill!

Early ride in other direction with Colonel Russell. Matheran such a nice place. Found Harry Parker located on the hill with wife and two children; he came to ride and dine.

Returned by 8.30 train to Bombay. Wellesley and I to dine with Commander Jenkins and officers of Indian Marine.

Wellesley and I to call on Governor. Among letters by the mail, received the following from my brother-in-law Stephenson.

Rooksbury, Fareham, Hants,

September 20, 1857.

My dear Harry—You are an Admiral and a K.C.B.; that rejoices my heart.

I transcribe for your information what has occurred in this matter, as it will please you, in some points.

August 29, 1857.

It is with very great reluctance and some pain that I request your careful attention to this statement, and that you will favour me with an interview.

[16]

The matter of painful grievance is this—

A public, professional, and personal disparagement, I may say dishonour, has been inflicted upon Captain Keppel, R.N., in withholding from him the K.C.B. of the Baltic.

There exists at the Admiralty a minute of more than twelve years standing, “that he was entitled to the C.B. for services performed in the China Seas under Admiral Parker and Sir Hugh Gough, G.C.B.”

Keppel gave up the command of the finest ship in the navy, St. Jean d’Acre, to serve in the trenches. His predecessor, Lushington, in the command of the Naval Brigade before Sebastapol, upon giving up his command was gazetted on the 10th July 1855. “Captain Stephen Lushington, R.N. to the K.C.B.”

He was not previously a C.B.

Keppel from that time to the fall of Sebastapol commanded that Brigade. The General and the Admiral Commanding-in-Chief in their despatches eulogised the services of Keppel in the highest terms of praise.

He commanded at the fall of Sebastapol, which was the crowning victory of the campaign.

Lord Lyons told me that the French could not have taken Sebastapol but for Keppel’s well-directed fire.

His rank of captain is not sufficient excuse. Lushington was gazetted as captain, and when the distribution of the honours were gazetted there was one captain his senior and one his junior K.C.B. (I have had a correspondence with Panmure and Sir Charles Wood upon this subject.)

I regret, and it is with painful regret I state it, that I can only collect from Wood the “stet pro ratione voluntas,” and that not very courteously given—but let that pass.

The Government had an historical name, a great naval reputation, in Keppel’s case. I beg to challenge contradiction to my statement.

Keppel has added to his naval fame, he ranks among the bravest and ablest captains in the British Fleet.

It cannot be said of him that he has received any honour for his distinguished services in the chief command of the Naval Brigade.

Many officers, when the list was published, and since the peace, and the widows of officers who never saw a gun fired, [17]have received the K.C.B. who have no claim superior to his; do not misunderstand me, that I express any disapprobation that such distribution has been made, I only wish to express the pain I feel—that services less than his have been considered by the Government as deserving of a higher reward.

The Government intends to place before the public men deserving of its respect when these honours are conferred.

In giving to the immediate predecessor in the same command and before the final victory the K.C.B., and withholding it from Keppel, the Government inflicts a stigma on Keppel as being unworthy to receive that which is bestowed upon his immediate predecessor.

I do assure you that extreme surprise and regret are freely expressed by the highest, the ablest, and by a numerous body of the navy at this unmerited stigma.

Keppel does not know of my writing this letter to you. I have known him from a child. I am deeply pained at the publick disparagement.

The recent demonstration at Portsmouth shows the estimation in which he is held by both services. Why should the Government ignore his merit?

Will you, as an old friend, give me some explanation?

On 27th August I received the following from Panmure:—

“My dear Steenie—The only bone between us is removed. I have taken the Queen’s pleasure in making Harry Keppel K.C.B.—Yours

(Signed) Panmure.”

God bless you, my dear Harry.

Ever your most devoted brother,

Hy. Fred. Stephenson.

[I hope I may be excused for inserting this letter, but I can honestly declare that I had forgotten its existence until the present moment, 27th June 1898, when in turning over a heap of bygone manuscripts I came across it by accident.

H. K.]

[18]

Took leave of my kind host and hostess. 4 P.M., embarked on board Madras (P. and O.) hired transport; weighed at sunset.

Left the Madras at Suez by rail to Cairo; wheels running on inverted iron saucers about five feet in diameter. Embarked at Alexandria on board P. and O. Ripon for Southampton. Among passengers was Mrs. Moir, the widow of a doctor who had been killed by the mutineers, six hundred miles up country. She lost one of her children in her flight, but found it at Calcutta in the care of a friend who had picked the child up on the road. Lieutenant Campbell was also a passenger. He had made a wonderful escape from the mutineers at Fyzabad. The mutiny and its horrors, hairbreadth escapes of our friends, the courage of the English women, and the heroic work of Colin Campbell, Henry Havelock, Outram, Windham, and many more gallant soldiers, was the only subject of conversation on board the steamer.

On December 6 arrived at Southampton. Joined invalid wife at Bognor.

At Holkham; where we remained until end of year.

[19]

England

After a few days between brother Edward and friend Eyre we arrived in London. Brother Stephenson, as deputy-ranger, placed the lodge in Hyde Park at my disposal, which exactly suited the poor invalid. The approaching wedding of the Princess Royal with Prince Frederick William of Prussia caused the early winter months to be unusually gay. I hardly like to mention the names of those who were kind to me under the delusion that I had taken care of their sons in China.

Was at the state ball, Buckingham Palace, previous to the royal wedding, which took place on 25th.

Dined with Her Majesty, Buckingham Palace.

Dined with Rajah Brooke.

The hunting season was now in full force. Having invested with Tilbury for the hire of a couple of horses, “Alice” and “General,” with groom, at £30 a month, he to replace lame ones; off to my nephew Edward Coke, owner of Longford in Derbyshire. Determined frost, giving me time to examine horses; both appeared well up to my weight, and good jumpers.

Wenny Coke put in an appearance. Frost [20]continued the next ten days, making me wish Mr. Tilbury had the horses in his own keeping.

Change of wind, but none of weather.

Rode Alice to Ingestre. Kindly welcomed by my old friend Shrewsbury. Took up my quarters. Walter Talbot staying here. Fine old place this Ingestre—peacocks about.

Taken to dine with the High Sheriff, P. Williams, at Stafford.

Ditto weather. Rode General with Walter Talbot to Bifield, Lord Bagot’s. Cokes there, and Grosvenors—Lady Constance, Di Coke, very pretty.

Returned to London.

Dined with Admiral Rous, a pleasure often enjoyed. His parties were always sporting, I never missed a race within reasonable distance. My good elder brother could not understand why I was so fond of “seeing a fool in red riding after a rogue in yellow.”

Was getting into the train at Portsmouth, when my faithful old coxswain, Spurrier, stopped me with, “Think I have found Lord Gilford’s watch.” During the two minutes of the train’s starting, he explained that last evening his wife was in one of the numerous haberdasher shops in Portsea; a well-dressed woman came in and wanted a smart yacht shirt for her friend. On being shown the usual seaman’s shirt, she wanted something much smarter; her man had a gold watch and chain that he was proud of, and that Admiral Keppel had given him a cheque for £10 only a few days before. Poor women! how fast their little tongues will run.

The giving the cheque I perfectly remember, as well as the man I gave it to. To go back for a few months before the little affair of the Fatshan Creek. [22]The splendid crew of the Raleigh were divided into cruising boats and captured many suspicious Chinese junks, some laden with cargo; but owing to the scarcity of interpreters they were generally condemned and their property confiscated. In the end the prizes amounted to a sum of money: not much, if divided among all the ships, but a nice little bonus for the captors. On my being promoted and ordered home, the captors of strings of pice agreed that I should take charge of the money, converted from pice into sterling bills, which I was to divide, as I thought proper, among the wounded or most deserving characters invalided home. A man belonging to my wounded boat’s crew was one of the recipients.

On arriving in London I went to Lord Clanwilliam’s house in Belgrave Square and ascertained the number of the gold chronometer watch he had given to his son on leaving England. The bill, receipted, was soon found. I then had to find my friend Sir Richard Mayne, the Chief of Police. He found an intelligent detective, to whom I gave my late coxswain’s address at Portsea.

Three days afterwards, leaning over the rails in Hyde Park, a suspicious-looking character, whose appearance I did not quite approve, rapped me on the shoulder and beckoned me to join him. Great was my relief when he informed me he had Lord Gilford’s watch. Getting him to accompany me to Belgrave Square, on the way he informed me that he had gone to Spurrier’s house; they went together to the shop where the girl had bought the shirt, but they had seen no more of her. Walking back, although dusk, Mrs. Spurrier spotted the girl on the opposite side of the street. The detective accidentally placed himself, in a way they have, and seeing a respectable girl [23]asked if she had relations in the Navy—the Admiralty had sent him down to seek proper objects for employment. I need not say that in a few minutes he had the state and condition of the man with the yacht shirt. His respectable parents lived on the Isle of Wight, etc. The next day detective found his way to the parents’ house and had an interview. On his way back he met Jack in the best of spirits rolling along; after a few minutes’ talk the detective abstracted the watch saying, “No. 8471: the one I was looking for.” Two assistants crossed over from the opposite side. By this time we were at Belgrave Square. Lord Clanwilliam much pleased; also poor Lady Clanwilliam, who was an invalid, but her pleasure was followed by distress as to what would become of the poor wounded man. I proposed to her Ladyship that I should return the watch to the poor fellow and her regrets for the trouble she had given him! When I got below, the detective told me that the man would be brought up before the magistrates on the Wednesday following. If no witnesses appeared he would be discharged. A tenner from Lord Clanwilliam to the detective ended the business. Curious that a watch stolen in China, April 20, 1857, should have been recovered by a detective in Portsea in the same month of this year.

Visit to Lord George Lennox at his “Bleak House,” Southsea. While there, was invited to the charming Goodwood for a few days.

At United Service Club we entertained the Duke of Malakoff at dinner. The Raleigh’s crew had meanwhile arrived at Chatham. The dog, Mike, in addition to his performance at Fatshan, was at the storming of Canton, where he had a scaling-ladder to himself [24]and wore two medals. His appearance was enough to clear the battery; the Chinamen fled, except those stopped by bullets. Lord Lansdowne was fond of dogs as well as music. At his request had Mike brought up from Chatham, and he was much admired. He had been given me by Captain Michael Quin, hence his name, who was paying off while Raleigh was fitting out at Plymouth. Mike was unhappy away from a ship. He was returned to Chatham, and attended working parties on shore: I had not the heart to remove him. The months April, May, and June brought me into a society to which I had been unaccustomed. Although I enjoyed it, it hardly comes within a sailor’s life.

Attended Her Majesty’s ball.

As the following is copied from an old engagement book and can interest near relations only, I advise my readers to skip this and try next chapter.

My pretty niece Annie Garnier married Colonel Edward Newdigate.

Cheery dinner at “The Ship,” Greenwich—Admiral Milne, James Blyth, Charles Eden, and Colonel F. Campbell.

Dined, Skinner’s Company.

Lady Palmerston’s evening.

Dined with Duchess of Richmond.

Dined with Lady Downs.

Dinner with Merchant Taylors.

Dined with Sir John Thorolds. Evening, Duchess of Norfolk.

[25]

70 Cranbury Park for Bibury Races, with Tom Chamberlain. Have not time to describe the place here, but in it were four beautiful pictures by Romney of Lady Hamilton. Chamberlain’s son was in the Balaklava charge. On the retreat his horse was shot under him. He quietly took the saddle off, put it on his head for a protection, and calmly walked into camp. My sister Caroline, who was staying with her father-in-law at Bishopstoke, wrote me about a pretty cottage for sale. On my arrival there I found a small sylph swinging on the entrance gate, a daughter of Mr. Peter Wells. I bought the place, with some good Italian furniture, for £1500. There was a full-length picture by Swenton of a beautiful lady, occupying one end of the dining-room: this was the mother of my young friend Zöe on the gate (now Lady Brougham and Vaux). The lady was one of a handsome family, such as artists delighted in; the background of the picture was of trees, painted at Windsor Forest.

Dined with H.R.H. Duke of Cambridge.

Dined with Fred Gye, lessee of the Royal Italian Opera, Covent Garden. At his charming house near the Thames one met a varied society—Prince Leiningen, Prince and Princess Victor of Hohenlohe, the Countess Gleichen, Meyerbeer, statesmen, authors, painters, singers, actors: it was indeed a cheery centre. After dinner we always adjourned for dessert to a glass room 120 feet long, delightfully cool in summer, flowers and plants growing; the ladies left the table to sit further away in this same room. Gye used to give me passes to the theatres. I was one night arranging baskets of flowers between banks, where fairies were supposed to be resting, when the curtain suddenly ran up faster than I could get to [26]the wings. But though he was a stern disciplinarian “behind,” Gye forgave me.

Poor Gye’s terrible fate is fresh in my memory. He was shot accidentally while on a visit to Lord Dillon, and died near the covert side: sportsman that he was, he always wished to be buried in one. His sons have all made their mark. The eldest, whom we used to call the “Baron,” married Madame Albani and went on with operatic management. Percy is a judge. Herbert went into the Navy and served on the China station under me in 1869. Another son was in the Artillery. His daughter, Clara, I often see.

Dined with Lord Alfred Churchill.

Evening, Lady Palmerston. Dinner, Sir Anthony Rothschild.

Balls at Duchess of Hamilton’s and Lady Caroline Maxe’s.

Dined with Sir William Middleton. Evening, Lady Pigot’s. During summer had been improving my pretty, but small place at Bishopstoke, on the bank of the river Itchen. The place suited me down to the ground. The stabling, which I rebuilt, was perfection.

Dinner with Mr. Newdigate at Blackheath.

Dinner at Navy Club, entertaining First Lord.

Luncheon, Duchess of Somerset. Dined with Lord Methven.

Dinner with Duke of Newcastle. Evening party, Duchess of Manchester.

Review at Aldershot.

Lady Mayoress’s reception.

Luncheon with Ranelagh. Dinner, Lord Sandwich. Evening, Lady Jersey.

[27]

Early dinner, Lady de Clifford. Later to Cremorne Gardens.

Lunch, Lady Shelley.

Dinner Admiral Walcott. Party Lady Rokeby, and ball at Duchess of Wellington’s.

Among friends I always received kind welcome on board Sir Thomas Whichcote’s schooner yacht Enchantress. Towards the end of the season I was with him at Cherbourg, where we had gone to witness the Naval Fêtes, and the inauguration of the new railway. Her Majesty and the Prince Consort arrived on the 4th August, accompanied by Lords of the Admiralty and a brilliant staff. Received by the Emperor Napoleon III. and Empress Eugenie. The next morning, at breakfast time, I took up the newspaper and read the sudden death on 30th July, at the Earl of Fife’s Seat, of my beloved brother-in-law, Stephenson.

To be alone in my grief, I landed and strolled by the side of the road up the hill to the high ground. As if to distract my thoughts, I met a French cavalry regiment marching up, their brass band playing “Rule Britannia.” Was off by the 4 P.M. steamer to join my poor sister Mary, who with her children was staying at Folkestone. The death had indeed been sudden, heart complaint, while sitting up in bed.

September found me shooting with Sir Thomas Whichcote at Ashwarby in Lincolnshire.

Beautiful day and lots of birds—wild, of course, they always are. With our four guns bagged 180 partridges, 18 hares, 1 rabbit—making 199 head. Whichcote did things well; as kind a host as man could have. A good hot luncheon. Ditto dinner. Very jolly.

Another fine day. Same party; bagged 204 [28]partridges, 18 hares, 1 rabbit. Haunch of venison for lunch and other good things.

Dirty weather with rain. Held up late, but high wind. Same party; 131 head of game. Much pleased at receiving a letter from Lord Palmerston stating he had recommended me to Her Majesty for the appointment of Groom-in-Waiting.

Better weather, but high wind. Still lots of birds. Same four guns; 200 partridges, 17 hares, 1 rabbit—218 head! Finish to four good days’ sport, to say nothing of the evening meal.

Party breaking up. Freke and I in dogcart to Lincoln. I to London.

Up from Portsmouth. Put up at Westbourne Terrace. There had been some cases of smallpox near my chambers. Wandered about. Tabooed for fear of infection.

By 11 A.M. train to Bishopstoke. Found sister Caroline and family at the Dean’s. Forgot all about the smallpox and embraced the children!

Busy rearranging Bishopstoke.

By afternoon train to Southsea. Received by George Lennox at Bleak House. Party to dinner. The good George Greys, etc.

Went over to Ryde by 12 o’clock boat. Back with George Lennox to see the Michael-Seymours before dinner.

By 11 A.M. train to Bishopstoke. Dean off again to Rooksbury. Sleep to-night in our own cottage.

By train to Southampton. Met George Lennox. Went on board Pasha, a Sultan’s yacht, very gaudy. On board Ripon, starting for Alexandria with Indian passengers. George Lennox back with me to Bishopstoke.

[29]

George Lennox off to Portsmouth, and I to Sir Francis Barings at Stratton. Found Pelhams and Nevilles. Tom Baring and wife.

Should have had some good shooting had the leaves been off the trees. Six guns; 110 head.

George Lennox and I in Gilman’s carriage to Winchester; great luncheon at the Dean’s. Party there. Lord Palmerston from Broadlands. Garniers from Rooksbury. Gilman taking us back to Bishopstoke. By train to Portsmouth. Put up at George Lennox’s.

Business at Admiralty. Dined with Rodney Mundy’s mother; nice cheery old lady.

By 4.30 train to Godstone. Found Rajah recovering from his sad paralytic stroke.

Took early leave of Brooke. Returned to Bishopstoke.

Found invitation to dine at Broadlands; unluckily for yesterday.

Colliers to dine.

By 3 P.M. train to London.

To Westbourne Terrace. Seconded resolution made by Bishop of Oxford on Gospel in China. Meeting at Willis’s Rooms. Much amused at Strand Theatre. Our Marie Wilton a little darling.

By Great Western to Berkeley Castle, to Admiral Sir Maurice Berkeley. Extraordinary old place. Not all the conveniences of modern houses, but made up for in association. Castle wall left as knocked down by Cromwell.

Mounted by Sir Maurice. Well appointed pack. Huntsmen and whips, etc., dressed in yellow velveteen. Best run of the season; I mounted on “Lord William.” Mrs. Berkeley and Mrs. A’Court to dinner.

[30]

Afternoon, inspected twenty-seven good hunters. Hounds out for a walk. Handsome pack.

By special train. Hounds and all, horses, servants, etc., to Gloucester. Meet about five miles beyond. Mounted on Pearce’s small black horse. Good hunter.

Capital mount by Armytage on one of his “jobs” from Carey. First-rate run and I in good position throughout. Baring of Cheltenham arrived.

Baring, Armytage, and I hedgerow shooting. Sport not much. Mrs. and Miss Canning arrived; very tall. Mrs. Berkeley charming.

Shooting to-day something more like; plenty of foxes too.

Mount again on Pearce’s little black horse. Carried me right well throughout a longish day, one fall into a lane. Have greatly enjoyed my visit to Berkeley Castle.

By early train to get across to Peterboro’ and Huntingdon. On a visit to Hinchingbrook. Colonels Knox and Vyse and wife, Annie Lady Montagu, and niece Emily Leeds, etc.

Shooting order of the day. Six guns; 189 head. Duke of Manchester good shot. The charming Duchess came to dine.

Mounted by Lord Sandwich to meet Lord Fitz-William’s hounds. Fog too thick to draw a fox. Provoking—uncommon well mounted. The Manchesters left.

Up early, mounted by Lord Sandwich, to breakfast at Kimbolton. Lord Cowper there. To meet the Oakley. Did not find till late. Left to ride 22 miles home.

Mounted by Sandwich to meet the Cambridgeshire. Nasty wooded country. Foxes, but no getting away. [31]Rode to station and returned to London by 1.30. Dined with Rokeby. Met the Manchesters.

By 3 P.M. train to Bishopstoke; lost my purse between station and home, containing £9: 10s. Horrid bore!

Spent Christmas at Bishopstoke.

[32]

England—Groom-in-Waiting

Saw the New Year in at the Southampton Yacht Club House with George Lennox, having dined on board Turner’s yacht.

Received enclosed:—

(Copy.)

Broadlands, 18th January 1859.

My dear Admiral Keppel—If you should happen to be disengaged on Thursday, would you come over to us on that day and stay and help to beat a cover on Friday.—Yours sincerely,

(Signed) Palmerston.

To Broadlands.

At Broadlands, shooting.

Dined with the Gilmans, meeting my old friend Pereira of Dent’s House, Hong-Kong.

Wife and I by train to Winchester. The good Dean sending to meet us. Party to dinner.

To Winchester to appeal against property being assessed at £80, when it was £50. Gained appeal.

Augustus Leeds brought over the sad news of Lady Sandwich’s sudden death. Sad indeed! Planted a couple of deodars on bank of river.

Train to Winchester. Dean entertaining judges and grand jury at dinner.

[33]

Dressed at my tailor’s; attended Her Majesty’s levée.

By train to Sleaford and Ashwarby—Whichcote sending for me. Got two hunters from Percival at Lincoln. Welby to stop.

Meet the Duke of Rutland’s hounds at Haverholm, occupied by the Dowager Lady Winchilsea, the beautiful Fanny Rice. Short runs with two foxes. Bad scenting day; ground dry and hard. Got one cropper!

No hunting. After luncheon another walk. Looked over ground, where some rasping jumps had been taken.

Marquis of Tweeddale kindly placed his horses at my disposal.

Hounds met at Glinn, Welby’s place. The Drummonds and many friends there. Killed two foxes; but a bad scenting day.

Meet at Fulbeck—Reverend Fane’s. Rode Percival’s horse, wilful brute; though a good jumper.

Meet at Turner’s. Mount from Lord Tweeddale, in addition to my Percival; a short run in afternoon.

Took leave of Tom Whichcote, etc. He appears to have everything a man could wish.

Arrived at North Creake for wedding. Miss North and her sister Catherine, and their cousin, Sara North, splendid girl of seventeen.

Party increased by George and Augusta Keppel. Twenty-two to dinner. Everything well arranged.

Auspicious day arrived—sun shining, fourteen bridesmaids. Edward performed. Stand-up breakfast, seventy or eighty attending.

General dispersion. Took up abode with Astleys: [34]she charming. Two Miss Lee-Warners and Bobby Hammond to dinner.

Mounted by Astley with Lord Hastings’ harriers: very good fun. Mrs. Astley’s riding first-rate: she does everything well.

Train to Diss. Met there by brother Edward. Dogcart to Quidenham; friend Edward and Mrs. Eyre to meet me at dinner.

Eyre and wife taking me to Harling Station. To London. Dressed at Four Swans, and dined at Fishmongers’ Hall. Had to return thanks for the Navy. Put up at friend Dunn’s, Lowndes Square.

Dined with Clarence Paget.

By 11 train, meeting Mark Wood at King’s Cross. To Grantham. Walked to Syston. Party, Lord and Lady Middleton, two Miss Reynardsons, Miss Beaumont and brother, Reynardson, Wood, Gibbs, Hillyard and his wife, Cole, Fox, and Whichcote. Jolly. Cook, first-rate.

A regular fall of snow. Party hunting nevertheless. Grantham Hunt Ball good fun. Went with the Misses Fane.

Great meet of the Belvoir Hounds; with Thorolds in their brougham. Mounted on a roarer, saw part of a very good run.

Croxton Park Races. Show of vehicles from Syston. Box seat with Reynardson on his drag. Races fair, and weather as usual. Bitter cold. Picked up £15.

Finish to an agreeable week at Syston.

I never had time to attend to politics, but born of a Whig family throw in my chance with kind friend and honest politician, Sir Francis Baring. Stood with him for Portsmouth. After a week’s chaffing and riotous living, I found myself at bottom of poll! The [35]difference between Whig and Tory now: one is dead, and the other extinct!

At Lord Denbigh’s.

With Dunne and party to the great Derby race. Won by Hawley’s “Musjid.” Dressed and went to Her Majesty’s concert.

On return from Epsom found at club telegraphic message of my wife’s sudden illness. Arrived at Bishopstoke 11 P.M. The poor wife had a fit at 6; unconscious since.

A succession of fits during the day. My true friend Eyre here in answer to telegraph.

Georgina Crosbie arrived in evening an hour before the sad end.

What could I have done without friend Eyre?

The last sad ceremony performed by the Dean of Winchester in the Parish Church. Her brother William and two sisters, my clergyman brother, Edward and Reverend Edward Eyre attended, and the good Rajah Brooke had a bouquet laid on the coffin.

Welcome to Larling from friend Eyre.

At Quidenham Parsonage with Edward.

Misfortunes never come singly. From Bombay hear of Sussex Stephenson’s serious illness.

[36]

In Waiting

First appearance as Groom-in-Waiting at Osborne. Her Majesty, with the Prince Consort, had gone to Balmoral, leaving the younger Royal children, Prince Leopold and Princess Beatrice, in charge of Lady Caroline Barrington. Never was an Admiral who felt so proud of being a groom. Lady Caroline came of a stately family. As we walked into dinner I felt myself smaller than I really was.

Carriages and steamers were at her ladyship’s disposal; it was interesting to see how quickly the charming young Prince learned to acknowledge the sentries’ salutes as we passed.

Delightful as the land excursions were in that beautiful island, I felt more at ease when her ladyship proposed a trip on board the Fairy steam-yacht commanded by my friend D. Welch, who handled her as if she had been a jolly-boat. We went into Southampton Docks at a pace which puzzled me. Lady Caroline kindly proposed a trip in carriages up to my pretty cottage at Bishopstoke, where I had the honour of providing tea. H.R.H. the Duchess of Kent was residing at Norris Castle. Lady Caroline and myself went three evenings in the week to make up a rubber of whist. H.R.H. was the only person who always [37]lost. We were paid in the brightest shillings, polished for the occasion.

My term of waiting was only too soon over; I was relieved by Colonel Cavendish.

I was again in waiting at Windsor Castle, having relieved Colonel Kingscote. Adjoining me were Captain du Plat, Equerry to the Prince Consort; and Captain George Henry Grey, Equerry to the Prince of Wales; these young men were old friends and agreeable companions. I took my two hunters and put them up at Windsor. Everything was new and interesting to me. Late, when we retired, my friends the Equerries kindly came to my room to enjoy their smoke. In the mornings we used to assemble in the corridor, and there wait for orders, riding, shooting, or whatever was going on.

One morning the Equerries were wanted to attend H.R.H., while I had permission to amuse myself, which I did by a ride in Windsor Great Park. It appeared that the Prince Consort, having bought some pictures in London, wanted a fit place to hang them. Passing through the Equerries’ rooms, H.R.H. came to mine. I was, as stated, out riding. The Prince immediately smelt smoke, and remarked, “The little Admiral told me he did not smoke.” My friends only smiled, H.R.H. was never undeceived! Once, when riding was the order of the day, I rode my best hunter. On crossing one of the streams, the Prince of Wales proposed that I should try my horse over the river instead of the bridge. I got over, but my horse made an over-reach and struck my right heel, which gave me pain. It was in 1840, when my father was Master of the Horse, that a boy was found concealed in a room adjoining Her Majesty’s. Since then, it had been the custom, when Her Majesty [38]was about to retire, for the Groom-in-Waiting to precede, and see the coast clear. My foot gave me pain, and I had taken up a spot in advance, when these horrid Equerries, whom I had not forgiven about the smoke, picked me up, and having planted me in the right place, disappeared. I made a proper bow when Her Majesty passed, and almost forgave my playfellows about the smoke! The Prince Consort had introduced the Christmas Tree, and we used to dance the Old Year out and the New Year in, to the tune of the “Old English.” When the clock struck twelve, the band suddenly struck up “God Save the Queen.” Everybody was very hot, and everybody kissed his partner except myself. I had the honour of dancing with Her Royal Highness the Princess Louise.

[39]

The Cape Command

At Windsor Castle. Ladies-in-Waiting—Lady Caroline Barrington, Hon. Mrs. Bruce, and Lady Ely, while the Maids of Honour were Hon. Beatrice Byng and Hon. Emily Cathcart.

Shooting with the Prince Consort were the Prince of Wales and Duke of Cambridge, while in attendance were Colonel F. H. Seymour, Major-General Hon. R. Bruce, Captain George Grey, Colonel Clifton, and myself. Earl de Grey was of the party.

Finished my turn in waiting by hunting with the Prince Consort’s harriers.

To Berkeley Castle. Kind welcome from Sir Maurice and Lady Charlotte.

Hounds met at Sir G. Jenkins’s, who gave me a good breakfast. Woodland country; plenty of foxes killed.

Wild-goose shooting: novel and interesting, but hard work.

Hunted from Berkeley Castle. Colonel “the giant” in great force.

Daily hunting; foxes often found in trees!

My appointment to Cape command. By rail to London; put up with sister Mary Stephenson.

Forte, commissioned by Captain E. Turnour; [40]Commander V. C. Buckley joined. Officers and men joined by end of week. Ship being manned by drafts from various ports; not allowed to enter seamen for ourselves.

Sunset, hoisted flag, white at mizzen.

Saluted flag of Commander-in-Chief, Vice-Admiral Edward Harvey. Issued contract; made clothing according to recent regulations, hats included: a mistake.

Had some difficulty in getting Admiralty to exchange the heavy old launches for the new forty-foot pinnaces which are now supplied to all other ships. Considerable difference in the stowage of this ship and that of the Raleigh.

Joined Marquis of Queensberry, naval cadet, and Mr. Stephenson, mid. Dockyard people building a small poop for the accommodation of the captain, secretary and flag-lieutenant—the poop not to show above the hammock netting, and not to occupy more of upper deck than just abaft the after gun. Screw to be raised as in line-of-battleships: the best arrangement under all circumstances that could be made.

Cabins had already been fitted for the conveyance of Sir George Grey and staff. An order to prepare cabins for Lady Grey and maid, coming so late, deprived me of half my accommodation.

In consequence of Her Majesty’s kind consideration, attended at Windsor as Groom-in-Waiting.

Attended confirmation of Prince Alfred. Lord George Lennox as Lord of Bedchamber to the Prince Consort.

Forte left Sheerness for Spithead. Cheered by the Norfolk Militia.

Prince of Wales left for the Continent, attended by Hon. R. Bruce and Captain George Grey.

[41]

My little happy holiday over, Her Majesty kindly hoping to see me back. Rejoined Forte at Spithead and rehoisted flag. Salutes exchanged with Admiral Commander-in-Chief Wm. Bowles, C.B. Was informed that on way round from Sheerness a leak was discovered in the screw aperture.

Steamed into harbour; secured alongside Sultan hulk. Transported guns forward and all heavy weight to discover the leak.

Ship taken into steam basin, preparatory to being docked. In taking her in, dockyard people managed to carry away jib-boom. No smoking allowed; shifted ship’s company to Victorious hulk.

Hauled into No. 7 dock, dockyard people stopping leak.

Hauled out of basin, only just in time, ship hung in entrance. Another two minutes, and she must have grounded, as well as two three-deckers. Sundry sheets of copper were rubbed off on port side. Obliged to heel the ship to repair damage.

Came to at Spithead.

Noon, weighed, running for the Needles.

10 P.M.—Came to in Plymouth Sound.

Exchanged salutes with Commander-in-Chief, Vice-Admiral Sir Barrington Reynolds, K.C.B. 3.30 P.M., having embarked His Excellency Sir George and Lady Grey, Captains Speke and Grant, African travellers, friend Boileau, and others, weighed and left the Sound.

3 P.M.—Came to in Funchal Roads, Madeira. While steaming in exchanged salutes 13 guns, with Flag-Officer Inman, whose flag, blue at the mizzen, was flying on board United States corvette Constellation, the first United States “Officer’s Flag” we had seen. Saluted also the Portuguese flag with [42]21 guns, and English Consul Erskine on his leaving the ship.

Ship was visited by Lord and Lady Fortescue and family, also my kind friend of long standing, the late Consul, Mr. Stoddard. As soon as they were landed, weighed and made sail.

Celebrated Her Majesty’s birthday by a dinner on the poop. At 8 P.M. that celebrated old beast, Neptune, hailed the ship, burning lights, etc., and then came on board amidst the usual downfall of water, and promised to pay his respects on the morrow to all such as had not before passed through his dominions, comprising three-fourths of those on board. He then took his departure for the night, to the relief of some and inconvenience of all, amidst fire and water-works, the light of his car being visible astern for an hour afterwards.

His Oceanic Majesty came on board and performed the usual ceremony.

10 A.M.—Steamed into Rio de Janeiro harbour. Returned salute from Madagascar. While running in, and after coming to, had to return and exchange no end of salutes. Brazilian Flag, 21 guns; Admiral’s salute, 13; French man-of-war brig, 13; and Prussian Commodore, 13.

Passengers disembarked and proceeded to Petropolis. Tribune, 31, Captain Geoffrey Hornby, arrived from Pacific and exchanged salutes.

Passengers returned. Weighed and stood out of Rio harbour.

12.5 P.M.—Henry Hill, seaman, fell overboard while the ship was going 10 knots under sails and steam. Cutter fitted with Clifford’s admirable apparatus for lowering was down in the shortest time and the man saved.

[43]

[44]

An untoward event occurred during the first watch. Under extreme pressure from Captain Turnour and the surgeon, who stated that the Governor would either commit suicide or murder his wife, I consented to return to Rio Janeiro, and reached that port on the evening of the 12th. Next morning, having landed the Governor, Lady Grey, and maid, sent an officer to know when His Excellency would be ready to embark. He sent word he was then ready, and that if I would not write home what had occurred he would not. I kept my word.

Sailed, and arrived at Simon’s Bay on 4th July, 8 P.M. His Excellency was in such a hurry to convey to Admiral Sir Frederick Grey the fact of his arrival, that, unseen, he dropped himself into a shore boat and landed at Admiralty House.

Landed, after usual salutes, to pay respects to Admiral Sir F. Grey. I mentioned the Governor’s message to me at Rio, to the effect that if I would not write home what had occurred he would not. I ascertained that in his statement to Sir Frederick he made out that the proposition not to communicate home came, in the first place, from me to him. This untruth accounts for my subsequent treatment.

The Forte requiring a thorough refit, shifted flag to my friend Captain Algernon de Horsey’s ship, the Brisk, and with our travellers, Speke and Grant, prepared to visit the East Coast.

[45]

Cape Command—Flag in Brisk

Embarked with Flag-Lieutenant and Secretary. Hoisted flag on board Brisk, Captain Algernon de Horsey. Received with yards manned. Embarked Captains Speke and Grant, with his guard of 100 Hottentots, volunteers from the Cape Mounted Rifles; also 12 mules, the Cape Parliament having voted £300 to purchase them for the interesting expedition. Sailed at sunset, leaving Forte with Captain Turnour in charge. Rounded to on signal.

3 P.M.—Came to in 9-1/2 fathoms off the mouth of Buffalo River. The township of East London on the south entrance composed of storehouses and other new and neat-looking buildings. At the end of a substantial stone wharf stands a lighthouse to correspond—not mentioned in the charts; it showed a bright fixed light. The town is communicated with by a surf boat hauled to and fro over the bar by means of a hawser, one end of which is attached to an anchor outside; as uninviting a coast to approach as can be imagined. Should a railway or any good road for the conveyance of the produce of the country be established to Algoa Bay, the Port of East London may prove unworthy of the name it has assumed. At 5 P.M. weighed, proceeded under sail.

[46]

No observation yesterday, but those of to-day at noon showed that the current for the last 48 hours had been south-west. 97 miles. Proceeded making particular survey of coast.

Came to at 4 P.M., in the magnificent Bay of Delagoa, about 7 miles from the entrance of the river. Sent a boat in to communicate: but more to ascertain what might be doing in the slave way.

Landed at daylight on the Island of Shefeen; more for the purpose of hauling the seine than shooting; nevertheless took my Whitworth rifled carbine. Observing along the sand prints of a small cloven foot, which I took to be that of the pig, Algie Heneage and I struck into the bush; stunted trees, but in places tolerably clear underneath. At first there was little to attract our attention beyond sundry paroquets and an occasional pigeon, for the destruction of which we were not prepared.

I fired once at some distance at what I imagined to be rabbits, playing about at the edge of the jungle, but they were too nimble for me. It was while on our return towards the beach, where we expected a breakfast of fresh-caught fish, that a beautiful antelope bounded across our path. It was large for an animal of that species, a dark reddish-brown colour. I was now satisfied that the numerous footprints that we had seen were not pig, but those of deer. The jungle being too thick for us to beat, or even see many yards into, proposed that we should conceal ourselves in any likely-looking shady spot, with sufficient clear range for a fair shot.

The ground was dry and the air clear of mosquitoes. We had been quiet for about a quarter of an hour, when I observed an antelope approaching, apparently unconscious of danger, nibbling the bits [47]of herb or grass that grew up between the dead leaves, when within twenty paces of our position it stopped to feed, broadside towards us. It was a full-grown doe. I observed her pretty head with its beautiful large black eye, and not wishing to spoil what I intended to have stuffed as a trophy, I raised my rifle and aimed, so as to hit her just behind the shoulder. Heneage was ready, knife in hand, to cut her throat, when I pulled the trigger; the lock snapped, and in a moment my beauty bounded into the jungle. I had forgotten to put a cap on; the rifle was a breechloader, to which I was hardly accustomed. Our disappointment can well be imagined.

We remained a short time longer in the same spot, hardly hoping that anything else would come near us. Now these antelopes, with their spindle legs and tiny feet, make no noise, but on looking in the direction I observed a whole troop of small monkeys, whose curiosity had brought them to ascertain who the intruders were who had so disturbed the quiet of their domain. They had spread themselves over some width of ground, and were advancing with all the caution of so many diminutive riflemen. When within about fifty yards one of those in advance made us out and gave notice.

They came to “general halt,” which was followed by a general chatter, and I could observe each small round head peeping from behind the stump of bush or tree where it had taken shelter. Theirs were little black faces, surmounted by a white fringe, which somewhat resembled the frill of a woman’s cap. The body was green, belly white, and tail long; however, as they did not appear inclined to make a further advance, sent a bullet at the head of one who appeared [48]to have the command, and I was glad to find that I had only struck the stump of the bush behind which he had concealed his active little carcass.

Their curiosity having been gratified, they scampered away on all fours, chattering and closing together as they went along. We never saw them on either bushes or trees, which caused me to think that those small things were the same sort I had a distant shot at in the morning, and must have been monkeys and not rabbits.

We soon shifted our berth some little distance to a spot affording a tolerable range, considering the denseness of parts of the jungle, and made ourselves comfortable, perhaps too much so, as after a while I started from a reverie to a pinch from Algie, and from the quarter pointed at could just see the round red back of an antelope moving towards us. I held in my breath as it approached. Unfortunately I had laid aside my rifle. The motion to lay hold of it was sufficient to cause the creature to raise its head, and the noise of the loose steel ring on the stock of the cavalry carbine made it dash into the bush, where it was out of sight in an instant.

It would be useless to describe the number of chances we had or the number of deer we might have bagged if something had not happened.

Our last chance occurred when we had agreed to take up positions on separate mounds, covered with brush and stunted trees, two-thirds round, about twenty yards in width, round which was a fair open space of long grass. In less than half an hour we observed a fine antelope come out of the jungle within ten yards of where I knew that Algie must be lying. It stopped and looked about, and I saw that it was about the size of a calf, but with the thinnest legs; [49]so delicate and slender as to appear unfit to support the round, plump body it had to carry. Watched, expecting every moment to see the beautiful creature bound into the air and fall to the report of Algie’s gun. However, it walked leisurely—stepping a trifle lame with the near hind leg—across into the opposite bank.

I had my rifle to my shoulder, but Heneage had been so kind in allowing me all the former chances, I thought it would not be doing the handsome if I deprived him of this, the last and only one he would have. When I inquired how he had come to allow so good an opportunity to pass, I found he had just awoke from a pleasant sleep.

We returned on board, amused and interested, but having had a blank day, did not boast. De Horsey, in pulling up the Tenby river, saw a hippopotamus, but he had no gun with him. The Governor informed us that there were plenty of rhinoceros as well as elephant in the neighbourhood. I noticed a magnificent pair of tusks in his room.

[50]

East Coast Sport

After leaving Delagoa Bay it was not much out of our way to pass the small island of Europa, said to abound in turtle.

We made it at about 9 P.M. on Thursday, August 2. The moon was at its full. Although a partial eclipse darkened it for a while, by the time we were off the north end of the island the moon shone out in full splendour. It was thought that nothing would be easier than to heave the ship to and send a boat in and bring off as many turtle as we required. At 10 P.M. a party shoved off in the cutter, and shortly afterwards Heneage, O’Rorke, and self left in the galley.

We found a sea breaking on a reef that bounded the coast, but farther to the west the breakers became smaller as we got under its lee. A coral reef extending along the coast a full half mile from the shore was clearly distinguishable. Watching our opportunity we got on to shelving coral, it being dead low water, and then found that we had a good quarter of a mile to haul her over water which varied from nothing to six or eight feet with deep holes. However, these were made clear by the light of the moon, and nothing was left but to haul the boat over, or [51]return on board. The water deepened into a comparatively clear space between it and the shore, forming a sort of lagoon. The boat was easily pushed through this, and we landed shortly after midnight.

Leaving the remainder to light a fire and prepare for a night’s bivouac, O’Rorke and self started along the beach to the westward to look for turtle. Although there were the tracks of many in the sand, we had travelled two miles before we came to marks that appeared fresh. A large turtle had been coquetting about, as is their wont, in search of a fit spot in the dry sand to deposit her cargo of eggs.

In this instance, it was evident that the old lady had been difficult to please, as after many turns and windings the track led again inland; and sure enough, ten yards from the beach, then about eight inches deep, appeared a small oval-shaped hillock, exposed by day to the heat of the sun. It was evident, when we got alongside, the turtle was sleeping away the time until the rising tide had lifted her high enough to allow of her proceeding to sea for further amusement.

The first she must have known of our presence was by the feel of our hands under the outer edge of her shell—a sort of tickling under the ribs—by which we endeavoured to turn her on her back. This she resented by striking out with all four fins, and not only covering O’Rorke with sand and water, but sending me sprawling on my back. Luckily she was aground.

O’Rorke started into the jungle, returning presently with two branches, the best he could get, to act as levers, with which to turn her over. This was a far more troublesome job than we [52]expected. The weight of the brute alone was 360 lbs., and the strength of the foremost fins wonderful; however, after considerable twisting and manœuvring we managed, with our levers, to get her off side to the edge of a hollow about eight feet by six, and with this advantage, and a heave together, we turned her over. There she lay on her back flapping wet sand, but comparatively helpless. The tide was now rising, and there was nothing left but for O’Rorke to return to where we had left the boat for assistance, leaving me to manage the best I could. I suppose I am the first Admiral who ever kept the middle watch on a turtle. As the sea rose over the outer reef it came rolling in to where I was seated, and as each roller lifted my charge she renewed her struggles to get rid of me. Our object was to keep her head towards the sandy beach, which rose rather abruptly, by inserting one end of the lever, which was crooked, under her back and behind her fore fins when she raised herself up, which she did whenever a roller came to her assistance. To prevent her floating, I seated myself on her stomach. By these means I caused her to heave herself in nearer the shore, but in doing this I got so plastered with wet sand that I must have had the appearance of a small pyramid. At another time she gave me such a slap on the knee, I thought my leg was broken; the pain was great.

I never had so troublesome a watch; it appeared to me O’Rorke had been hours away, although the good fellow had run there and back. Having to keep 360 lbs. weight struggling to save its embryo family from being made into omelets, herself into “soups and steaks,” as I saw afterwards chalked on her back, was no small undertaking. [54]Nor can I describe my delight when some of the boat’s crew hove in sight. Another struggle with the brute and I must have given in or have been carried out to sea holding on to the hind fins, like my friend King George of Tonga Tabu.

Having secured our turtle, a further walk along the sandy beach, a bend to the S.W. brought us within reach of unpleasant smells, and close to a projecting point, within sight of the remains of a huge whale, from which rats, by thousands, were rushing towards the jungle; when the crabs, to say nothing of conger eels, cleared the bones of the monster, they fell to the ground.

We secured several joints of the backbone, which, when cleaned and covered with canvas, were formed into curious camp stools, in my garden at Bishopstoke. How the monster got where we found him, over the half-mile of coral-bound coast, we wondered; unless the unfortunate brute was thrown over the reef and stranded during one of those fearful hurricanes which visit these latitudes.

The shooting was not much. There were some goats running wild; the sire of this stock was described as a magnificent fellow, with an immense beard and strong smell. A few pigeons were seen, but so unaccustomed were they to the intrusion of human beings as to allow themselves, when fatigued, to be chased from bush to bush, knocked over by stones or sticks. The frigate birds, some black, visit these latitudes.

Much excitement was caused at low tide by our men chasing, between the openings of the coral, rock cod, conger-eels, and parrot fish—the latter of a brilliant green colour, some of them weighing four or five pounds.

[55]

5 P.M.—Came to in Mozambique Harbour in 5-1/2 fathoms. A berth that would suit the Forte. Care to be taken running in, in a long ship. Saluted Portuguese flag. Like most Portuguese forts, on a grand scale, but the guns are small and out of date; about 100 men. A few small vessels at anchor. Trade small, principally in ivory, rhinoceros horns, and ebony. Slaver in disguise. Was received by the Governor, Don Joao Tavares de Almeida, who did me the honour of dining with me on board. No Consul. One Don Joao de Costa Sourez most obliging.

7 A.M.—Weighed, made sail.

Having been in these seas before, I cautioned Captain de Horsey to keep a good look-out for slavers. We were running under sail with light southerly winds, and proposed fires being lighted and banked up. De Horsey was particular about desecrating the Sabbath, but in the afternoon a sail was reported. Later she was made out from the masthead standing to the eastward. I advised De Horsey to take his glass and see for himself.

Before he was half-way up the fore-rigging I gave the order to light the fires. The smoke had no sooner ascended than the look-out on the fore-top-gallant yard sang out, “She’s gone round without taking her studding sails in.” The wind fell light by sunset. We stopped engines under the stern of a fine rakish-looking ship. Lieutenant Adeane was sent on board, and took possession of the Manuela, formerly the Sunny South, a Rio packet of upwards of 702 tons. She had 846 slaves on board, and was waiting to complete 900 before proceeding round the Cape to Cuba. She had been hovering off the coast for weeks to complete her cargo. We sent her [56]into Pomony. I went on board, she was a fine-looking ship, seven feet between decks. However, on looking down the fore hatchway, the stench was intolerable. Sent prize in charge of Lieutenant Burlton to the Mauritius.

[57]

Zanzibar—Shooting Hippopotami

Arrived at Zanzibar. Having expressed a wish to see the hippopotamus in his native state, Speke, being aware of my weakness, kindly invited me to accompany him to where sport was almost a certainty. It was necessary to procure a dhow, on board which a party could live.

Our proposed trip soon got wind. An unusual noise throughout Sunday night on board the Sultan’s yacht was accounted for in the morning by one Captain Mahomet informing us, which we had been well aware of, viz. that he had been all the night bending sails, and half the morning bastinadoing his crew; he stated he had received orders to convey me across the channel.

From this infliction I, however, excused myself, as well as from that of the company of the half-civilised, drunken rogue who commanded her. Through the kind influence of Colonel Rigby, Luddah, a Banyan, British subject, and head of the Customs, placed at our disposal a new dhow, with a captain and fourteen Arabs. Hoping to expedite their movements, Speke, Heneage, and myself embarked on Monday night, so as to start early the following morning; but at that time we were not as experienced in Arab [58]movements as we have since been. It commenced raining soon after we got on board, and on our taking shelter below we found the deck overhead leaked, and the stench from the bilge water sickening. We got under weigh at 10 A.M.; at 5 P.M. anchored in an extensive bay off a village called Kesooku. About the bay were shoal patches of sand and several small islands with mangrove bushes, over the roots of which the tide flowed when up; it was on and about these islands that we expected to find our game.

We were welcomed to the village by a Bombay Banyan Chief. Having given us a refreshing drink from green cocoanuts, he cleared out part of a store hut for our accommodation. We made up our beds outside on stretchers under the shade of the projecting roof.

It appears that the habits of the hippopotami are to land at night for food, betaking themselves to the retirement of the small islands before break of day. Such unwieldy brutes cannot travel on shore without leaving marks, by which they are easily traced, and generally return to the water by the same paths. As they are never molested by the natives, we thought we might intercept them before they went to rest, and intended to be up at 3 o’clock, but it rained and our native servants neglected to call us. We went later to try for guinea-fowl, which were said to be plentiful and excellent eating. A covey of them was seen but not got at.

Our next plan was to proceed to the patches of islands in the bay, so as to reach them before low water, about which time our experienced friend, Speke, considered that the hippopotami would be more likely to be caught napping or basking in the mud. We approached the islet with caution.

[59]

[60]

I shall not forget the first wild hippopotamus I saw: a huge ugly brute, standing up to his middle in water, apparently indifferent to our approach, until within fifty yards, when he moved leisurely towards some rocks where the water was deep and disappeared. On rounding the rocks, we opened on an extended sand-flat and observed several Sibuko, half in the water, with one fine fellow standing separate. To the left, and within forty yards of him, was a small clump of trees. As soon as our boat grounded, took up my position, as prearranged, on that side, and stalking under shelter of bushes, got pretty close, with a rest for my gun. Speke and Heneage had spread out to the right, so as to cut off his retreat that way to the sea. Within forty yards, when I thought they were quite ready, I fired my first shot. The monster seemed more astonished than hurt, although a stream of blood from the side of his neck showed where my ball had told. While he hesitated, the others broke away in a parallel direction to that I was moving in. They were close together, the head of the Hippo nearest to me being a little in rear of the shoulder of his companion. Had my double-barrel smooth-bore ready. It does not often fall to the lot of man to get right and left shots at a brace of hippopotami. I took the nearest; hit him just behind the ears, struck the spine, and brought him on his knees. The thick skull of the other turned my second ball.